Have you ever wondered why people believe in the weird and the supernatural?

My guest today certainly has.

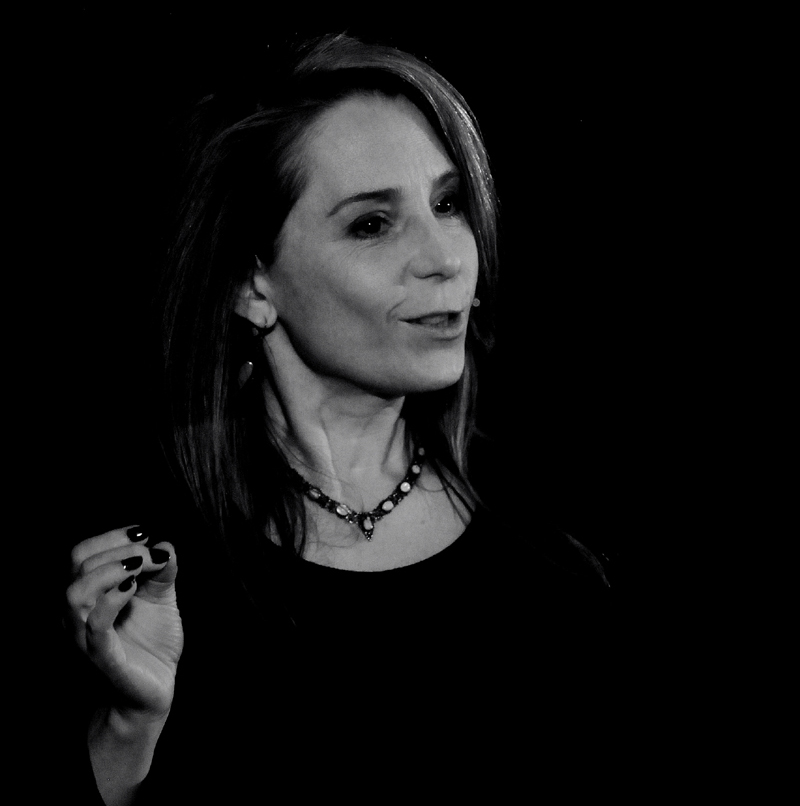

Deborah Hyde, folklorist, skeptic and former editor of The Skeptic Magazine, has spent years unravelling the mysteries behind ghost Stories, Legends and bizarre historical events.

0:36

She credits her fascination with a supernatural to a childhood surrounded by mad aunties, and now applies psychology and history to understand why these tales endure.

By day she's worked behind the scenes in film and TV, even finding herself on the wrong side of the camera now and then.

0:57

But by night, she's digging into the strange and supernatural with a rational eye.

Today we're diving into one of the most peculiar medieval legends, the Green Children of Wolpit.

Who were they?

What do historical records tell us?

1:15

And could there be a rational explanation for their eerie green skin?

Stay tuned as Deborah's here to separate fact from folklore and explore what this story tells us about belief, history, and human nature.

1:37

Hi, Deborah, Thank you so much for joining me on the podcast today.

Hello Michelle, delighted to do.

You want to start by just maybe explaining first of all what sparked your interest in folklore and superstition and all things supernatural.

It's been with me for as long as I can remember.

1:56

I mean, since I was a kid.

So it's one of those things I think that if this is going to get you, it gets very young.

And my my family on my brother's side were very much believers in all this stuff and very sort of mysterious old women.

2:12

So I kind of started as a believer.

You can buy into all of this stuff.

And I think it was because it was all about, yes, now mystery and power.

And those are very attractive things for a child because they don't have any power.

And so it was just, it was just always fascinating and you know, the romance of castles and things like that.

2:35

We didn't like money, so we just used to go to old castles.

And it's.

So the way that it all ties into history was really potent for me when I was a child.

And I found a book called The Black Arts by a guy called Richard Cavendish when I was about 11.

2:52

And it was the first time that had introduced me to the idea that the attempt at magic, I'm talking about High Renaissance magic here, was an attempt at understanding and manipulating the universe.

It wasn't just a very hard nonsense sort of spewed mysteriously and ready before us.

3:11

This was people trying to understand the universe and it went from there really.

I have to say, I wasn't allowed to read the Black Arts.

I had to get on a chair and get the book and read it in quiet because it's not the sort of thing that most 11 year olds want to read.

3:30

It was a fascinating insight.

And from there I think the quality of my reading got better and better because obviously you can spend your whole life buying into this, but I thought it was far more fascinating to read analysis, you know, historical analysis of it.

3:45

And so as time went on, by the time I was I was into my early 20s, I didn't believe in all in any of it, but I still found the subject very fascinating.

So, as someone who is both a skeptic and a folklorist, how do you balance that appreciation for myths and legends with that rational approach to understanding them?

4:12

There are many folklorists are also skeptics.

I would say all of the decent ones really.

You've got to have a decent analytical brain on it because otherwise what are you going to believe?

You're going to believe in everything where wolves, ferries, Where do you stop?

4:29

The the thing that I think is so interesting about this subject, even if you are not religious or prone to believe at all, which I'm not now, then it really it isn't about fairies and vampires.

It's about humans.

4:45

It's about the way that we construct our world.

You can go into anthropology, you can go into history, you can go into literature, you can go into economies, the way that the way that societies functioned under certain circumstances to come up with the idea, these ideas that people constructed their universe with.

5:06

So when I was younger, it was really not a very respectable a line of investigation.

I'm very good friends with Professor Chris French, professor of anomalistic psychology at Goldsmith's University, and he for him it was the same where he had his respectable strand of psychology study.

5:28

But if you were studying anomalous phenomena, that is what people subjectively experience when they see ghosts and things like that, then it was, it was it was kind of like a little bit of a frivolous line.

Talk to Susan Blackmore, who's done so much for out of body experiences and alternate experiences, the same thing.

5:47

It's completely unrespectable.

When she was doing all of her work.

And I think certainly over the last sort of 30 years or so, academia has come to realise that this isn't about fairies, this is about people.

And we're going to be talking about quite a well known story, The Green Children of Wilpit.

6:08

Do you want to just give a brief retelling of that story for anyone who is listening who's unfamiliar with it?

This happened in the 12th century.

Most of the dating dates it to kind of the, the border of King Stephen and Henry the Second, which we put it in the 1150s, and there were two green children in Wallpit, which is in Suffolk, very flat part of the country, and they turned up at harvest time.

6:39

They had come out from somewhere underground, either from the edge of a pit or literally from the underground world, and they couldn't speak English.

Their clothes were made of a fabric that the people there couldn't understand and they were green.

6:55

That's the most peculiar thing.

So they were taken to the House of the local noblemen and they were offered food, but they didn't recognise any of it as edible.

When somebody went past with some green beans, which at this point in history would have been broad beans, Farber beans were the only ones that were in England at the time.

7:14

They signed that they wanted to eat those and they didn't seem to know how to get beans out of pods.

They tried to get them from the stalks at first, but once they got the beans out of the pods, they ate them voraciously and that's all they would eat for a while.

And eventually they started to eat our food.

7:32

And they learned to speak English, or perhaps just the girl did, because the boy died.

We don't know if he died before he learned to speak English or while he was he was still speaking a foreign language.

And they recovered their their colour and she said about how she had come from an underground.

7:53

Well, the accounts vary slightly.

So the boy died and the girls survived and went on to marry a man from King's Lean, which is a bit further north.

So you've got so many elements there and it's obviously very, very peculiar.

8:10

The most peculiar thing is the fact that they were green.

How do you find people who were green?

Are there any historical records that exist that that document this event and how reliable are they?

Well, this is the thing that makes it so peculiar.

8:27

I think we'd probably not talk about it that much, except that there are two independent chroniclers who write it down.

There is Ralph of Cobbleshaw, and I was lucky enough to be able to go and see what remains of the Cistercian Abbey.

But he was Avatar.

It's integrated into a house cell.

8:44

And there's one part of it that was probably there while he was there in the 1100's, the late 12th century.

And he wrote a kind of, I think it was a slightly optimized view.

He has slightly more mythological elements in, and he's a little bit more believing in this kind of thing when you're at Newbrough.

9:05

Oh, and I should say covershall is in Essex, northern Essex.

It's not that far from Wall Pitts.

So Ralph attributes finding out about the story from a local nobleman, Richard d'account, to whom the children were taken.

So theoretically this is just once removed Ralph's account.

9:23

And we also have another account from a guy called William of Nouvera and he was based in an Augustan Abbey and he was further north in Yorkshire.

So and his account is a little bit more vertical, it's a little more down to earth.

And he says it's very peculiar, but he's heard it from several people.

9:42

So that's why he's giving it the time of day.

That's why he believes in it.

And it seems to be very much the kind of urban legend of its day.

You know, it was one of those things.

We're not the only people to transmit things virally.

9:58

It seems as though people back then did as well.

And of the internal evidence in the two accounts, the experts I've spoken to seem to think that they weren't kind of directly copying of each other.

They were each tape having their own tape on what was a viral story at the time.

10:21

So just thinking about then the the local geography of Woolpit, is there anything that would challenge or contribute to the to the plausibility of this tale?

There are so many things that are interesting about this tale.

10:36

The geography of Woolpit, it's on it's it's in Suffolk and the East Anglia goes low counties facing the continent were in very close contact with the continent, with the low countries on the continent.

So the idea that this was a load a bunch of Ghana Bouvieros who were making that some ridiculous various stories is can be discounted because E Anglia was in very close contact with Europe and there were educated people there.

11:06

There were lots of people there.

They did very well with the cloth trade from Flanders and there were lots of foreigners living in the area.

So it was a very cosmopolitan kind of area.

That's the most interesting thing.

This wasn't some little backwater somewhere at the top of the mountain.

11:23

And the second thing is that both accounts give accounts of the children coming from from below.

William is a little more sober.

He reckons that they they take, they were found near wolf pits.

These were ancient earthworks by the side of the of the village sofit to the East Village that were intended and actually to catch wolves.

11:46

They've actually found Roman artifacts and so we don't quite know what they're called, but they're very ancient hits.

And Ralph explicitly is still coming from an underground world with with caves and a city of dark, you know, sort of semi summit world.

12:06

And the interesting thing about Suffolk is that it doesn't have any claims.

It's brat.

So if you'd have been writing in Derbyshire about this, we could have said, OK, he's just buying into the local landscape.

But he really is taking what is a very, very strong mythical element and putting it into this story in a geographical position where it doesn't really belong.

12:34

So just thinking broader, are there any other kind of known stories either from England or or elsewhere that resemble this particular story of the the green children of Wilped?

There are, there are a few and for example, William Mcnewborough writes about people diagnosing for the day.

12:58

So you've got breaking a social contract.

It's about a social violation.

And he he lived during a phase called the Anarchy.

The king had a daughter, Matilda, and he gave her this crown and said that she should be the next monarch.

13:17

But a lot of people fought for her cousin, King Stephen.

So we had King Stephen in the early 12th century.

We had King Stephen, but it was a period called the Anarchy.

And unlike some civil wars, it really did actually truly affect everyone in the end with two of those, some ended up becoming the next king from one of the second who was who was one of our our best ones really.

13:39

So William lived through a period of of utter upheaval.

It was it was awful and the social norms were being violated.

So it seems that he was writing some of these supernatural stories to sort of to illustrate that.

But youth have others.

13:55

I think it was Gerald of Wales wrote about a wherewith couple who were were wolves because of a curse and they needed woman needed the last rites before she died.

So freeze trying to give her her last rites and she took her with costume off and then she sort of I think she did back up again before she died or something.

14:15

But in that case it was a well wolf story, but it was as a result of the curse rather than a contact with the devil.

So there were all sorts of stories like this.

If you have to emphasize, people weren't stupid.

They didn't know the difference between reality and and fable.

14:33

They didn't have the same access to to knowledge that we did.

So they didn't know whether werewolves could be real, but it meant something in a, in a, in a literature sense.

And they didn't know if there were other worlds under ours.

14:50

And, you know, they might have been.

So they did try to tell the difference between reality and fable.

And so we ended up getting a lot of stories and we had to try and place them.

Were they moral tables?

15:06

Were they literal returns of some factual accounts?

Or were they meant to be fables?

So how then would you say that this story fits within the the wider fairy folklore and medieval legends of that particular time frame?

15:25

Well, this is an interesting one because we might think that fairies are one thing.

And really if you trace the historical origins of them, there's over 1000 years of literature and mythology there.

15:41

And if you're not careful and try and compress them into one entity and they they just don't bring on.

One of the things that I've enjoyed most about doing my recent podcast is that I've got to speak to a couple of really good experts on this whole subject.

15:59

There's John Clark has written about the grandchildren of pulpit specifically, and Francis Young has written about the origin of very folklore.

So if you look at that, if you look at the podcast, you can see just how different our beliefs about fairies were in the 12th century to the way they were in perhaps the 6th century or the 16th century.

16:22

Indeed, Francis Young investigated the idea that fairies were amalgam of all sorts of things, that they were the remains of Romano Buddhist gods that remained after the the retreat of the Roman Empire in the 5th century.

16:38

And then after that, of course, you have Anglo Saxons coming in and for them a more appropriate word was elves.

You have these rather you have these kind of powerful themes that they were like tricksters that were clinically very dangerous in having lost elements.

16:55

How many?

So I think by the 20 grandchildren work it happily.

You've also got a big class difference.

We have for a while people didn't keep records in local English.

This was after the number one conquest.

So you have an outcoming on people from the continent and it will for them people writing in Latin and and speaking in in normal French and they have a different culture essentially to the commoners underneath them.

17:27

In addition, all of the stories that the depth from commoners are through the filter of a different class.

So people don't write things down first hand.

So we, we just, we don't know what normally people thought about elemental spirits or spirits around them.

17:46

They come through these filters.

Certainly the the fairies that we have later on, the kind of fairies of Shakespeare's Midsummer Night's Dream are an amalgam of a great many traditions, including the the romance and literary traditions of that anger normally.

18:05

And the wings came a lot later.

Probably the earliest you can find reference to fairing wings is sort of that would be 16% I suppose, but they've got really popular 1819 century.

So if you're not careful, we can compress these firmly complicated and varied ideas into one and try to extract what you want from the green children wall pit and it doesn't fit.

18:34

So what do you think then?

Tales like this one can help us to understand and serve society today.

You know, what can we learn from them?

What's it still telling us about life in the 12th century?

I think what it tells us about our own stories is that urban legends and viral transmission of stories has been around for a long time and that you don't get political accounts of factual events very well.

19:09

You, you've, you could have a camera and a microphone right there in there.

People don't even remember them.

Even if you ask 2 witnesses to on witnesses to something, you know, you asked for a year later that their accounts will probably bearing or even worse than that, if they did vary initially, they'll, if they've spoken to each other, they'll conform because they've spoken to each other and formed new memories and effect from exchanging stories.

19:34

So I think this can tell us that we, you know, we're prone to making stories, that the stories are there for a purpose and that they will change according to who's telling them.

19:50

As I said, the you know, William and Ralph would both educated higher class men because they were they were literate and they were churchmen and they were talking.

About events that had happened to lower past people so we don't know what they would take in from it.

20:06

Life in the 12th century.

It was very, very stratified and so you would, you know, receive the green girl went to work in the household and submitted to calf.

20:22

She was well said that she was still alive many years later, but that she was always wanting an impudent and you didn't have to be particularly anti social as a woman in the 12th century to attract that kind of label.

She could have just been a bit assertive.

20:40

You know, I think it's just a very good insight on to the fact that people were trying to tell the difference between history and fable.

So what are some of the the leading theories then that attempt to explain this particular story?

20:58

Well, John Clark goes through a lot of this in his book and he he takes each element individually.

And I think you have to because you can't necessarily just take the whole story at face value and try to put that into some kind of context into which it doesn't fit.

21:14

The first thing to tackle, of course, is why was a green?

I mean, it's a peculiar colour.

And John Clark goes through several of them.

It was he was wondering whether or not it was because they had a deficiency anemia, which can give you a sort of vaguely I'll colour.

21:34

He he makes particular, he lays particular emphasis on the fact that Ralph at one point uses a word which kind of implies a very dark bright green rather than a green around the heels type thing.

So we don't know what kind of green they were and we do know that it disappeared and we do know that those chronic has attributed it to a change in diet.

21:59

So they weren't looking for mysterious reasons.

They thought it was that there was some kind of health issue which was fixed by better living.

The theories about them not recognizing the language, that's a really peculiar one because as I say, this wasn't some gullible backwater.

22:16

This was a very this was a very cultural part of the world.

They were directed arsenal banks and locals would have spoken in various bandits of early English with English they would have recognized, you know, they could have recognized the sounds of German.

22:37

So the thought that those alignments which they just didn't get is really peculiar.

It suggests that the children came from purple afield, and writing ideas that I'm examining in the podcast series is that they really came from a power field, but they were perhaps Jewish or Muslim.

22:56

They come from the Middle East somewhere.

So what we don't, we don't really.

The point is we don't actually know.

You can't tie this one up nicely into a little parcel, but you can say that it's an interesting insight on 12th century life.

23:15

Yeah, and I think it's partly the mystery that makes it so enduring, isn't it?

It's such a such an interesting aspect, the fact that here you have have an account with children who have this green pallor to their skin.

And yeah, the fact that you can't tie it really neatly together in a bow and have the answers so easily there to explain it all.

23:37

There are so many different possibilities that make it so fascinating and intriguing.

And like you said, it just allows us to have this lens into a particular part of the world at a particular time and the people within it and the stories that they are telling, It's, it's fascinating.

23:55

Yes, I think that's the value of it.

There's the kind of this romantic fairy story and there's the idea that you're growing into a past world, and there are the ideas that people are coming from underground as well.

I mean that, you know, there's a lot of British frightful to suggest that in fact, Jasmine Briggs, who was a great student of of very social suggesting that this was somehow a kind of a reference to ancient religion on and relationships with the dead.

24:26

Most people have had some kind of supernatural relationship with the dead because it's very, very difficult to believe that someone has simply gone just because they've stopped breathing.

I mean, when you when you love someone and they just, they just pass and there's still a body there that's particularly hard to believe.

24:45

They're just bad.

And relationships with the day feature so heavily in so much religion that it would be a miracle that haven't happened in in Britain as well.

That certainly you know that I mean there were barrows built for and that's where I've built kind of 3000 or 7 news BC a little bit more than that.

25:10

And these were certainly rather mysterious to later people.

For example, we've got quite a slowly on the motorway that's very, very old as work and it was called Violence Smithy because Vinland was was a Germanic taxi, kind of a mythological figure.

25:31

So we've got the people who we would think of as highly historical have taken something which is more historical still and integrated into their own functional and their own legends.

I did some filming in Ireland a couple of years ago and there are these, what we call fairy forts there.

25:50

And this was, these were very patrical things.

These were answers once you would have a certain or elsewhere you did this because the best way to sit someone raiding you was to have a fence and, and to have a body of water to pass across.

But people much from later on called the ferry points.

26:07

And so that this was a sort of a supernatural place where fairies gathered.

So we're not the only people to be projecting backwards onto what we see in the landscape and to try and make something mythological of it.

It turns out that also a lot of people have done it.

26:23

And the green children, well, part of their story is that they may well come from underground, which kind of speaks of fairy land and relations with the day.

And for me, this is the, one of the really fascinating aspects of, of exploring folklore, exploring history, exploring these kind of elements of the supernatural that kind of bleed through in storytelling because it speaks so much to belief systems and how humans interpret the, the unknown.

26:57

And, you know, I think we, we tend to look back on history and we look at individuals and groups of, of people at certain points in, in time and think, you know, how can someone possibly think this?

And how can this story be something that was believed and, and so on and so, so forth.

27:15

But I, I, for me, I think it shows this connection between our past and, and ourselves today, because I think we still do the same thing.

We make stories, we tell stories, we try and shape and understand things that are not known to us as human beings.

27:30

We don't like to, to be in the dark, to not have the answer.

And so here you have people trying to create answers, trying to bring together rational answers to explain to hypothesis, hypothesise and come up with systems that explain something that they can't, that they don't necessarily have the answers to within their own town landscape, culture.

27:56

Here is something to fill that void.

And I think that's, I think that's incredibly invaluable to explore because I think, as I say, I think it connects us to our past, but at the same time, it helps us to truly understand what people were thinking and feeling and what their day-to-day life life was like, what it was that for them were their concerns of the day.

28:20

And again, we can often see that there are similarities rather than differences.

Absolutely.

I think first of all, people aren't stupid, so they might come up with some really funky ideas, but they think the best with what they've got.

28:36

And the second thing is that there's only thing a man, there's only about them more important than being than knowing your past.

And that is to be able to predict the future because people in the past live a lot more on the edge than we do.

But I don't know about you, but I've recovered from food there.

28:53

I've said this.

That's virtually that's that's virtually unknown in history and quite unknown in a lot in the world today.

So we'd have to remember that people, people needed some sort of power over the world, and that included over a supernatural world as well.

29:12

And so these these models of the world kind of emerged partly from the way that our perceptual systems work.

And our perceptual systems produce a lot of errors that they're built for survival, not reality.

29:30

And in addition, because we're naturally storytelling creatures, we do the best with what we've got.

And it's it's good to be able to try and hold on to an idea of the world to see if you can what does he can fix it.

So we've obviously spoken about this story and, and some of the theories around it.

29:51

What is it that you particularly think you know for yourself happened here?

Do you do you think this actually happened as a as a starting point?

I definitely think something happened, yes, and I think that the story of the kind of dynamics of urban legend and creepypasta have got a lot to contribute to this because we can see that the stories are different in their different retellings.

30:17

Winning with Newburgh was very was very keen to place it in reality, although he was puzzled about how it could be true.

Ralph of Coggleshaw was, I'd be unashamed about putting the more legendary elements in as well, but they both definitely thought it had happened.

30:34

Ralph of Covershaw, bear in mind, had heard it what just once removed from Sir William de Cound, who had spoken to the children and who in whose household the girl worked for many years.

So I definitely think something happened.

A couple of children were abandoned.

30:53

They had, they certainly had a Peaky colour and it was a colour that shocked people there at the time.

So they definitely attributed it to a nutritional deficiency because both both writers attribute the change in colour to a more healthy colour through food.

31:13

And it's hard to say what the language they were speaking and the cloth they were wearing work because as I say, this was a very, this was a very well travelled part of the world.

This wasn't some backwater.

So the thing about this story which makes it so appealing for, for folklorists and for skeptics and all the people who want to hear about it is that we can't quite know.

31:37

I think we've had writers who've tried to really reduce it down to its facts and it it just doesn't quite get there.

Paul Harris had it had it down to a couple of children lost from cloth merchants from Flanders after their parents were killed and it kind of doesn't quite work.

31:55

But I really admire his ability to try and truly get down to the facts.

John Clarke has done the definitive version.

The fact is we can't know that.

Personally, I am sure that something happened and that it was remarkable enough to bother writing down.

32:12

So Deborah, just to kind of look ahead, where can people find more of of your work and follow along to to discover more of what you're doing?

Well if you type in Deborah Hyde to Google you'll probably find me fairly easily.

32:28

I'm on all of the socials and I've just started doing a recent series of videos.

I'm trying to I'm trying to do one a month.

There are probably 5 or 6 episodes on the Green Children of Wallpit so you can finally find me through the socials and then you'll be able to follow what I'm doing after that.

32:46

I'm kind of I'm out there and I'm easy to get.

And I will make sure, of course, to include all of those links so that if people want to follow up by, you know, coming and finding you on Instagram or finding your website or listening to your podcast, etcetera, I will make sure that links to all are available.

33:05

So that, you know, if you're looking at this via the website, there'll be those direct links there and likewise in the podcast description notes.

So, yeah, I encourage people to to follow up because you cover so many really, truly interesting aspects that yeah, I think it's, it's a fascinating, fascinating 1 to follow up with because as I say, there are so many things that you cover, so many topics of interest there that I think you dive into to give your approach and, and share your expertise and your research with.

33:37

The gift it keeps giving, really, I can't imagine ever running out of source material.

And it's really, really good to meet people and talk to them, you know, in events, when I do live events and that kind of thing.

Because I think so many people are into this stuff.

And it's just nice to be able to provide them with content that keeps them, keeps them happy, keeps them stimulated.

33:57

It's right.

And just to kind of follow on from that, are there any books, articles, talks that you might recommend for anybody listening who, again, if they're wanting to follow up and look into this particular story a little bit further, where would be some good places to maybe signpost them too?

34:16

For this particular story, I would say the definitive book has been written by a guy called John Clark and it's called Green Children of Royal Pitt.

There was also a really good article written by a guy called Paul Harris, and he tries to take a very practical kind of analysis of the green children of Wall Pit.

34:36

I think it falls down on a couple of practical issues that that his approach is really good.

If you're interested in the origins of fairies, Dr. Francis Young wrote The Twilight of the Godlings and I've got all of these credits on any of the YouTube videos because Francis and John both appear in those videos giving interviews.

34:58

If you're interested in general about fairies, then there are so many books to read.

You can't do worse than starting with Catherine Briggs, the fairies in traditional literature.

So she's, she sort of started off, I think she was one of the people in the mid 20th century who started off the whole respectable study of, of fairies.

35:19

So yeah, there's, there's loads of stuff out there and I give links underneath the video.

So just pop over there.

Thank you so much again for your for your time.

Honestly, it's been so fascinating to to talk to you.

If I could, I would start going into other areas and we could start talking werewolves and witches and magic and all the other things that keep me so avidly interested in what you share across your social pages and things.

35:44

Yeah, honestly, the doors always open.

I think we could, we could literally spend the next 100 years talking folklore and these kinds of accounts.

And yeah, they fascinate me.

So yes, thank you so much for your time.

Just to be able to talk.

This one particular account has been really, really interesting for me to get your perspective.

36:03

So thank you so much for your time, Deborah.

Well, thank you for having me on.

And I will say goodbye to everybody listening.

Bye, everybody.

Thank you for joining us on this journey into the unknown.

36:21

If you enjoyed today's episode, please subscribe, rate, and leave a review on your favorite podcast platform.

You can follow us on social media for updates and more intriguing stories.

Until next time, keep your eyes open and your mind curious.