The Devil’s Stone of Marston Moretaine

In the village of Marston Moretaine in Bedfordshire, stands a curious monument that has perplexed locals and visitors alike for generations. Known as the Devil’s Stone, this mysterious standing stone holds in its weathered surface a tale born of folklore, Sabbath warnings, and the ever-present presence of the Devil in the lives and legends of rural England. Time may have hidden the true origins of the stone, but the stories that surround it are vivid, enduring, and deeply woven into the identity of the village.

At first glance, Marston Moretaine may appear like any other English parish—complete with its historic church, winding lanes, and fields that stretch quietly into the horizon. But unlike most churches, the Church of St Mary the Virgin has an architectural quirk that has baffled historians and intrigued storytellers for centuries. Its bell tower stands detached from the main body of the church, a full fifty feet apart. Such a design is rare, and in the absence of an official explanation, folklore has eagerly stepped in to provide one—invoking none other than the Devil himself.

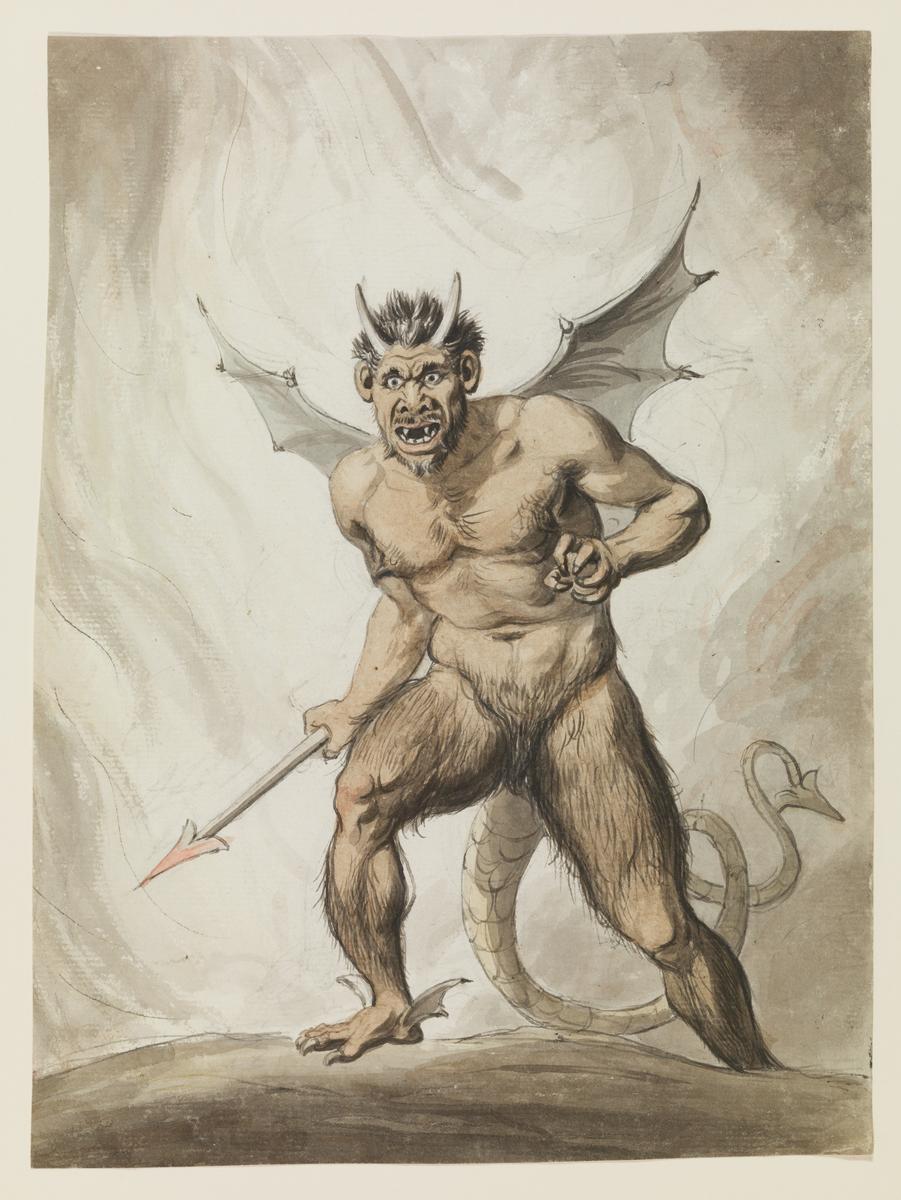

According to local legend, the Devil once roamed the fields near Marston Moretaine, up to no good as ever. Why he turned his mischief upon the church is unknown—some say it was built on sacred land he once claimed, others argue he simply resented the piety of the villagers—but one Sunday, he made an attempt to steal the church’s bell tower. With all his might, he heaved it from its foundations, determined to carry it away. But it proved too heavy. Frustrated, he dropped it where it now stands to this day, separate from the church, as if placed by unseen and cloven hands.

Yet this was not the end of the Devil’s antics. Eager to continue his wickedness, he turned his gaze upon a group of boys playing leapfrog nearby. It was the Sabbath, a day of rest and reverence, and games were strictly forbidden by the religious customs of the time. To break the sanctity of the Lord’s day was considered no light matter. The Devil, ever watchful for souls to claim, saw an opportunity.

The boys, unaware of who watched them, were engrossed in their game. One of them leapt over a curious stone—short, round, about three feet high—standing in the field. They laughed and cheered, each one trying to outdo the other. Then, a tall man dressed all in black approached them. He watched for a while, then challenged them to a game of leapfrog. Eager to impress and unafraid of this strange new playmate, they accepted.

The man stood upon the stone and beckoned the boys to leap over him. One by one they did, unaware of the danger. But once they had all jumped, the man revealed himself. No longer just a stranger, he stood in flames and shadow—his true form that of the Devil. With a cackle and a roar, he vanished, leaving only scorched earth and the smell of sulphur behind. The stone the boys had jumped was said to be marked by his feet, and from that day on, it was known as the Devil’s Stone.

Another version of the tale, recounted by Miss D.B. Ward in 1965, tells of a man seen one Sunday leaping and jumping in his own field—another violation of the Sabbath. The Devil, recognising the man as one of his own by such "monstrous crime," leapt from the church tower in a single bound, seized the man with unholy strength, and carried him off to Hell in another. The spot where this happened, it is said, bears a stone called the Devil’s Toe-nail, a stubby lump of rock forever marking the exact place of the man's descent.

Such stories abound in Marston Moretaine. The Bedfordshire Times and Independent, in 1873, told of a Sunday when several boys skipped church and wandered the fields. There they met a man in black who proposed a game of hop-skip-and-jump. The boys agreed, and the man made such a colossal leap—covering over forty yards in a single bound—that the children realised in horror that he was not a man at all. Terrified, they fled home and never missed another church service again. Stones were placed where the Devil's feet had touched the ground, and they remain to this day as silent testimony to the consequences of Sabbath-breaking and the Devil's unnerving agility.

As with all great legends, the story has grown and changed with time. Ernest Milton, writing in 1937, recounts that the tale was so frightening that the Abbot of Woburn had to visit Marston and perform a solemn ceremony to cleanse the village. Three stone crosses were placed to sanctify the ground where the Devil had jumped. One of these, believed to be part of an octagonal shaft, was visible for many years in a field opposite the local inn. It was said that you could see the shape of the Devil’s foot upon it if you looked close enough and believed hard enough.

The inn itself was not untouched by the story. On the road to the church stands the Jumps Inn—so named because it was on that very spot that the Devil made his infamous three leaps. According to Henry Bett in his book English Legends, it was there that three boys were playing when the Devil appeared and offered to teach them his supernatural style of jumping. After demonstrating three marvellous leaps that no mortal could match, the Devil revealed his true identity. He grabbed the boys and, in a sudden burst of blue flame, disappeared with them forever. The standing stones that remain are believed by some to mark the ground he covered in those unholy bounds.

This mingling of fact and folklore, myth and mystery, gives the Devil’s Stone of Marston Moretaine its enduring allure. Ask any local about the “Jumps” and you’ll receive a dozen different versions. Some remember three boys, others speak of one man. Yet all agree on the Devil’s role and his astonishing leaps.

These variations are not inconsistencies, but the very fabric of legend. Each generation adds its own colour to the tale, retelling it around hearths, at school, or in the quiet hush of the churchyard. It is in this way that folklore survives—not as a fixed truth, but as a living, breathing part of the landscape and the culture.

In truth, we may never know what first led to the peculiar positioning of the Marston church tower, or the true origins of the standing stone nearby. Perhaps the tower was built separately due to poor soil, structural limitations, or changes in architectural plans. Perhaps the stone is a remnant of an older, forgotten monument. But the villagers of Marston Moretaine have long preferred the explanation that involves a meddlesome Devil, three fearless boys, a blue flame, and the warning against skipping church on a Sunday.

As for the Devil himself, it seems that despite his strength and agility, he was unable to complete his plans in Marston. His footprints remain in stone, but his hold over the village is broken, warded off by crosses, prayers, and the quiet defiance of folklore itself. And the Devil’s Stone stands still—a silent monument to mischief, morality, and the remarkable leaps of both faith and imagination.

You can listen to guest Amy Boucher talking about Devil narratives in the folklore around Shropshire here: https://www.podpage.com/haunted-history-chronicles/the-devils-role-in-folklore-with-amy-boucher/

You can enjoy daily other accounts such as this and more over on patreon here: