Oct. 25, 2025

The End of an Era for SpaceX, China's Reusable Rockets, and Cosmic Conundrums

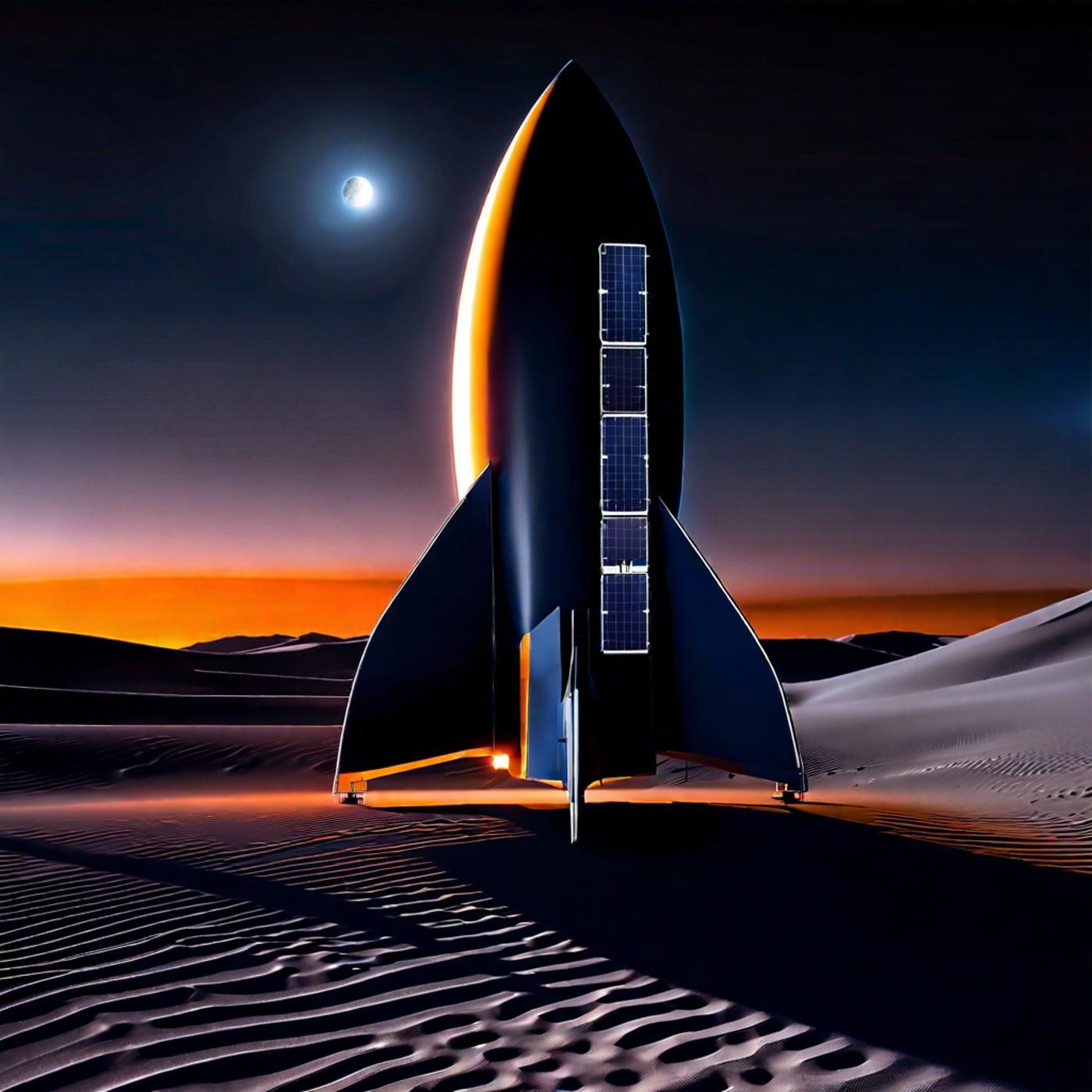

- End of an Era for SpaceX: SpaceX is decommissioning its original Starship launch pad, Pad 1, at its Starbase facility in Texas. This pad, crucial for early Starship development with 11 flights, has seen significant upgrades over the years and will be remembered as the birthplace of Starship flights.

- China's Reusable Rocket Ambitions: The Chinese company Landspace is making strides with its Zhuque 3 Rocket, a stainless steel, methane-fueled, reusable launch vehicle. They recently completed a successful static fire test and are targeting their first orbital flight test for late 2025, marking China's commitment to building its own space infrastructure.

- James Webb's Moon Discovery: The James Webb Space Telescope has observed a circumplanetary disk around an exoplanet 600 light years away, believed to be the birthplace of moons. This groundbreaking finding provides insights into planetary formation and the conditions necessary for moon development.

- Australia's Space Aspirations: Gilmour Space is gearing up for a second attempt at reaching orbit after their first flight was terminated due to an anomaly. A successful launch would make Australia the 12th country to achieve this milestone, signaling growth in the nation's sovereign space industry.

- Exploring Cosmic Mysteries: The episode dives into some of the biggest unsolved mysteries in space, including the Hubble Tension regarding the universe's expansion rate, the enigmatic fast radio bursts, the elusive nature of dark matter and dark energy, and the black hole information paradox. Each of these topics highlights the vast unknowns that continue to challenge our understanding of the cosmos.

- For more cosmic updates, visit our website at astronomydaily.io. Join our community on social media by searching for #AstroDailyPod on Facebook, X, YouTubeMusic, TikTok, and our new Instagram account! Don’t forget to subscribe to the podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, iHeartRadio, or wherever you get your podcasts.

- Thank you for tuning in. This is Anna and Avery signing off. Until next time, keep looking up and exploring the wonders of our universe.

SpaceX Launch Pad Decommissioning

[SpaceX](https://www.spacex.com/)

Landspace Zhuque 3 Rocket Development

[Landspace](https://www.landspace.com/)

James Webb Space Telescope Observations

[NASA](https://www.nasa.gov/)

Gilmour Space Updates

[Gilmour Space](https://gilmourspace.com/)

Cosmic Mysteries Overview

[Astronomy Daily](http://www.astronomydaily.io/)

Become a supporter of this podcast: https://www.spreaker.com/podcast/astronomy-daily-space-news-updates--5648921/support.

Sponsor Details:

Ensure your online privacy by using NordVPN. To get our special listener deal and save a lot of money, visit www.bitesz.com/nordvpn. You'll be glad you did!

Sponsor Details:

Ensure your online privacy by using NordVPN. To get our special listener deal and save a lot of money, visit www.bitesz.com/nordvpn. You'll be glad you did!

Become a supporter of Astronomy Daily by joining our Supporters Club. Commercial free episodes daily are only a click way... Click Here

WEBVTT

0

00:00:00.400 --> 00:00:03.400

Avery: Welcome to Astronomy Daily, the podcast that

1

00:00:03.400 --> 00:00:05.600

brings you the latest news from across the

2

00:00:05.600 --> 00:00:08.400

cosmos, as we like to say. Give us 10

3

00:00:08.400 --> 00:00:11.320

minutes and we'll give you the universe. I'm

4

00:00:11.320 --> 00:00:12.000

Avery.

5

00:00:12.240 --> 00:00:14.960

Anna: And I'm Anna. It's great to have you with us.

6

00:00:15.200 --> 00:00:17.680

We've got a packed show for you again today

7

00:00:17.920 --> 00:00:20.680

covering everything from historic launch pads

8

00:00:20.680 --> 00:00:23.480

being retired to incredible new discoveries

9

00:00:23.480 --> 00:00:25.520

by the James Webb Space Telescope.

10

00:00:26.040 --> 00:00:27.670

Avery: That's right, Anna. we'll be looking at

11

00:00:27.670 --> 00:00:29.950

China's progress on reusable rockets,

12

00:00:30.110 --> 00:00:32.870

Australia's orbital ambitions, and we'll end

13

00:00:32.870 --> 00:00:35.030

the show with a deep dive into some of the

14

00:00:35.030 --> 00:00:37.150

biggest unsolved mysteries in space.

15

00:00:37.870 --> 00:00:40.670

Anna: So let's get started. Avery. First

16

00:00:40.670 --> 00:00:43.310

up is an end of an era for SpaceX.

17

00:00:43.870 --> 00:00:46.190

Avery: It certainly is. SpaceX is

18

00:00:46.190 --> 00:00:48.870

decommissioning its original Starship launch

19

00:00:48.870 --> 00:00:51.070

pad, known as Pad 1, or

20

00:00:51.150 --> 00:00:54.110

Suborbital Pad A, at its Starbase

21

00:00:54.110 --> 00:00:56.700

facility in Texas. And this pad was the

22

00:00:56.700 --> 00:00:58.780

workhorse for the early days of Starship

23

00:00:58.780 --> 00:01:01.140

development, seeing a total of 11

24

00:01:01.300 --> 00:01:01.940

flights.

25

00:01:02.180 --> 00:01:04.740

Anna: It's amazing to think about the history made

26

00:01:04.740 --> 00:01:07.500

there. This wasn't just a simple concrete

27

00:01:07.500 --> 00:01:10.140

slab. It went through some massive upgrades

28

00:01:10.140 --> 00:01:10.820

over the years.

29

00:01:11.060 --> 00:01:13.710

Avery: Absolutely. it was eventually equipped with a

30

00:01:13.710 --> 00:01:16.550

full launch tower, a water deluge system to

31

00:01:16.550 --> 00:01:18.710

protect the pad from the intense heat of

32

00:01:18.710 --> 00:01:21.470

liftoff, and even the arms designed to catch

33

00:01:21.470 --> 00:01:24.150

and support the massive super heavy boosters

34

00:01:24.150 --> 00:01:24.870

for reuse.

35

00:01:25.220 --> 00:01:27.780

Anna: A true testament to their iterative design

36

00:01:27.860 --> 00:01:30.700

process. While it's sad to see it go, I

37

00:01:30.700 --> 00:01:32.660

imagine they need the space for the next

38

00:01:32.660 --> 00:01:33.540

phase of development.

39

00:01:33.940 --> 00:01:36.540

Avery: Exactly. They're moving on to bigger and

40

00:01:36.540 --> 00:01:38.500

better things with their new orbital launch

41

00:01:38.500 --> 00:01:41.020

site. But Pad one will always be remembered

42

00:01:41.020 --> 00:01:42.980

as where Starship learned to fly.

43

00:01:43.620 --> 00:01:46.540

Anna: Speaking of reusable rockets, SpaceX

44

00:01:46.540 --> 00:01:48.620

is getting some serious competition from M.

45

00:01:48.660 --> 00:01:51.500

China. The Chinese company Landspace

46

00:01:51.500 --> 00:01:53.460

has been making some impressive strides.

47

00:01:54.110 --> 00:01:56.870

Avery: They have. They're developing the Zhuque

48

00:01:56.870 --> 00:01:59.790

3 Rocket, which looks remarkably similar to

49

00:01:59.790 --> 00:02:02.790

Starship. It's a stainless steel, methane

50

00:02:02.790 --> 00:02:05.470

fueled, reusable launch vehicle. And they

51

00:02:05.470 --> 00:02:06.910

just hit a major milestone.

52

00:02:07.070 --> 00:02:09.909

Anna: The static fire test. Right. That's a

53

00:02:09.909 --> 00:02:10.670

crucial step.

54

00:02:10.990 --> 00:02:13.590

Avery: Right. They successfully completed a

55

00:02:13.590 --> 00:02:15.670

static fire test of the first stage

56

00:02:15.670 --> 00:02:17.990

prototype. This is where they fire up the

57

00:02:17.990 --> 00:02:20.190

engines while the rocket is securely bolted

58

00:02:20.190 --> 00:02:22.510

to the ground to testing the entire system

59

00:02:22.510 --> 00:02:24.070

under flight light conditions.

60

00:02:24.550 --> 00:02:25.830

Anna: So what's next for them?

61

00:02:26.150 --> 00:02:28.630

Avery: Landspace is aiming for its first orbital

62

00:02:28.630 --> 00:02:31.630

flight test in late 2025. This

63

00:02:31.630 --> 00:02:33.670

is all part of a much larger ambition for

64

00:02:33.670 --> 00:02:36.030

China, which is heavily investing in building

65

00:02:36.030 --> 00:02:38.830

its own space infrastructure, including a

66

00:02:38.830 --> 00:02:41.430

satellite constellation similar to Starlink.

67

00:02:41.670 --> 00:02:43.710

The pace of their development is really

68

00:02:43.710 --> 00:02:44.470

Something to watch.

69

00:02:44.790 --> 00:02:47.350

Anna: From engineering marvels on Earth to

70

00:02:47.350 --> 00:02:50.070

incredible discoveries far from home, the

71

00:02:50.070 --> 00:02:52.470

James Webb Space Telescope has deep done it

72

00:02:52.470 --> 00:02:55.070

again. This time giving us a peek into how

73

00:02:55.070 --> 00:02:56.390

moons might be born.

74

00:02:56.550 --> 00:02:59.310

Avery: This story is fascinating. Webb has

75

00:02:59.310 --> 00:03:01.870

observed a disk of material swirling around

76

00:03:01.870 --> 00:03:04.870

an exoplanet about 600 light years away.

77

00:03:05.270 --> 00:03:08.029

Anna: And this isn't just any disk. It's

78

00:03:08.029 --> 00:03:10.630

what's known as a circumplanetary disk.

79

00:03:10.630 --> 00:03:13.030

And it's the first time we've seen one that

80

00:03:13.030 --> 00:03:15.990

is rich in carbon. Scientists believe

81

00:03:16.070 --> 00:03:18.550

these disks are the birthplaces of moons,

82

00:03:18.790 --> 00:03:20.470

or exomoons in this case.

83

00:03:21.090 --> 00:03:23.380

Avery: So we're essentially watching a, moon system

84

00:03:23.380 --> 00:03:26.300

in the process of forming. Much like how the

85

00:03:26.300 --> 00:03:28.340

moons of Jupiter or Saturn might have formed

86

00:03:28.340 --> 00:03:30.300

in our own solar system billions of years

87

00:03:30.300 --> 00:03:30.580

ago.

88

00:03:30.980 --> 00:03:33.940

Anna: Precisely. The finding provides a, ah, rare

89

00:03:34.100 --> 00:03:36.380

real time look at the building blocks of

90

00:03:36.380 --> 00:03:39.060

moons and helps us understand the conditions

91

00:03:39.060 --> 00:03:41.980

under which they form. The power of the Webb

92

00:03:41.980 --> 00:03:44.540

telescope continues to unlock secrets of

93

00:03:44.540 --> 00:03:47.260

planetary formation that were completely out

94

00:03:47.260 --> 00:03:48.820

of reach just a few years ago.

95

00:03:49.350 --> 00:03:51.510

Avery: Lets bring our focus back to Earth now,

96

00:03:51.750 --> 00:03:54.350

specifically to Australia. The Australian

97

00:03:54.350 --> 00:03:57.070

rocket company Gilmour Space is gearing up

98

00:03:57.070 --> 00:03:59.110

for another shot at reaching orbit.

99

00:03:59.430 --> 00:04:01.870

Anna: Their first attempt didn't quite make it, did

100

00:04:01.870 --> 00:04:02.150

it?

101

00:04:02.470 --> 00:04:05.430

Avery: Unfortunately not. The flight was terminated

102

00:04:05.430 --> 00:04:08.070

shortly after liftoff due to an anomaly.

103

00:04:08.310 --> 00:04:11.150

But in the world of spaceflight, failure

104

00:04:11.150 --> 00:04:13.910

is often part of the process. The company

105

00:04:13.910 --> 00:04:16.630

has analyzed the data and is now targeting

106

00:04:16.630 --> 00:04:19.270

2026 for its second orbital

107

00:04:19.270 --> 00:04:19.670

attempt.

108

00:04:20.390 --> 00:04:23.190

Anna: It's a resilient industry. What does

109

00:04:23.190 --> 00:04:25.430

this mean for Australia's space program?

110

00:04:26.070 --> 00:04:28.870

Avery: It's a huge deal. A successful launch

111

00:04:28.870 --> 00:04:31.670

would make Australia the 12th country to

112

00:04:31.670 --> 00:04:34.590

reach orbit from its own soil. Gilmour

113

00:04:34.590 --> 00:04:36.710

Space remains optimistic and their

114

00:04:36.710 --> 00:04:39.230

determination is really fueling the growth of

115

00:04:39.230 --> 00:04:41.990

the nation's sovereign space industry. We'll

116

00:04:41.990 --> 00:04:43.750

be watching closely in 2026.

117

00:04:44.390 --> 00:04:47.330

Anna: All right, for our final segment, let's,

118

00:04:47.480 --> 00:04:50.440

let's venture into the unknown. Despite

119

00:04:50.600 --> 00:04:53.200

all our incredible technology and

120

00:04:53.200 --> 00:04:56.200

discoveries, space is still filled with

121

00:04:56.280 --> 00:04:59.160

profound mysteries that continue to puzzle

122

00:04:59.160 --> 00:04:59.720

scientists.

123

00:05:00.520 --> 00:05:03.160

Avery: My favorite kind of topic, where do we start?

124

00:05:03.800 --> 00:05:06.360

Anna: Let's start with the big one, the Hubble

125

00:05:06.360 --> 00:05:09.000

Tension. For years there's been a major

126

00:05:09.080 --> 00:05:11.960

disagreement on just how fast the universe

127

00:05:11.960 --> 00:05:14.720

is expanding. Measurements from the early

128

00:05:14.800 --> 00:05:17.320

universe, like the cosmic microwave

129

00:05:17.320 --> 00:05:20.120

background, give us one number. But

130

00:05:20.120 --> 00:05:23.040

measurements from the local modern universe

131

00:05:23.280 --> 00:05:26.120

using things like supernovae give us

132

00:05:26.120 --> 00:05:28.000

a different number faster.

133

00:05:28.800 --> 00:05:31.160

Avery: And the fact that they don't match suggests

134

00:05:31.160 --> 00:05:33.400

we might be missing something fundamental

135

00:05:33.400 --> 00:05:35.280

about the physics of the cosmos.

136

00:05:35.760 --> 00:05:38.240

Anna: Exactly. Next up,

137

00:05:38.400 --> 00:05:41.260

fast radio bursts or FRBs.

138

00:05:41.740 --> 00:05:43.820

These are incredibly powerful

139

00:05:44.060 --> 00:05:46.700

millisecond long bursts of radio Waves from

140

00:05:46.700 --> 00:05:49.380

deep space. We know they come from

141

00:05:49.380 --> 00:05:52.260

distant galaxies, but we have no idea

142

00:05:52.260 --> 00:05:54.900

what causes them. Theories range from

143

00:05:54.900 --> 00:05:57.340

magnetars to alien signals,

144

00:05:57.740 --> 00:05:59.660

but nothing fits all the data.

145

00:06:00.300 --> 00:06:02.230

Avery: A, true cosmic whodunnit.

146

00:06:02.630 --> 00:06:05.350

Anna: Then there's the giant elephant in the room.

147

00:06:05.930 --> 00:06:08.650

Dark matter. We see its gravitational

148

00:06:08.650 --> 00:06:11.290

effects everywhere. In the rotation of

149

00:06:11.290 --> 00:06:13.850

galaxies, in the bending of starlight.

150

00:06:14.170 --> 00:06:16.570

But we can't see the stuff itself.

151

00:06:17.050 --> 00:06:19.930

It makes up about 85% of the

152

00:06:19.930 --> 00:06:22.530

matter in the universe and we have no

153

00:06:22.530 --> 00:06:23.770

idea what it is.

154

00:06:24.410 --> 00:06:26.570

Avery: It's humbling to think that we've only ever

155

00:06:26.570 --> 00:06:29.210

observed a tiny fraction of what's actually

156

00:06:29.290 --> 00:06:29.930

out there.

157

00:06:30.250 --> 00:06:33.160

Anna: It really is. Lets touch on

158

00:06:33.160 --> 00:06:35.880

a few more strange ones. We recently

159

00:06:35.960 --> 00:06:38.960

detected the second longest gamma ray burst

160

00:06:38.960 --> 00:06:41.960

ever seen. It lasted for over a thousand

161

00:06:42.040 --> 00:06:44.840

seconds. We think these bursts come

162

00:06:44.840 --> 00:06:47.480

from collapsing massive stars. But

163

00:06:47.559 --> 00:06:50.120

one lasting that long challenges our

164

00:06:50.120 --> 00:06:52.920

models. Wow. Then there's

165

00:06:52.920 --> 00:06:55.840

Hoag's object. A bizarre galaxy that looks

166

00:06:55.840 --> 00:06:58.680

like a perfect ring of young blue stars

167

00:06:58.840 --> 00:07:01.480

surrounding an older yellow nucleus

168

00:07:01.640 --> 00:07:04.580

with almost nothing in between. We

169

00:07:04.580 --> 00:07:05.940

don't know how it formed.

170

00:07:06.340 --> 00:07:08.180

Avery: That sounds like something out of science

171

00:07:08.180 --> 00:07:08.660

fiction.

172

00:07:09.300 --> 00:07:12.100

Anna: And another great mystery closer to home.

173

00:07:12.420 --> 00:07:15.380

The hunt for Planet nine. The strange

174

00:07:15.380 --> 00:07:18.060

clustered orbits of several objects in the

175

00:07:18.060 --> 00:07:20.860

outer solar system suggest there might be

176

00:07:20.860 --> 00:07:23.740

a massive undiscovered planet lurking

177

00:07:23.740 --> 00:07:26.260

out there, 10 times the mass of Earth.

178

00:07:26.660 --> 00:07:29.380

But despite years of searching, we haven't

179

00:07:29.380 --> 00:07:29.860

found it.

180

00:07:30.580 --> 00:07:32.980

Avery: These mysteries are what make astronomy so

181

00:07:32.980 --> 00:07:35.780

exciting. For every answer we find, we

182

00:07:35.780 --> 00:07:38.500

uncover 10 new questions. The list of

183

00:07:38.500 --> 00:07:40.980

cosmic conundrums is seemingly endless.

184

00:07:41.460 --> 00:07:44.220

Take the Great Attractor for instance. It's a

185

00:07:44.220 --> 00:07:47.180

massive gravitational anomaly located in the

186

00:07:47.180 --> 00:07:49.220

direction of the Hydra Centaurus

187

00:07:49.220 --> 00:07:51.740

supercluster, pulling our Milky Way and

188

00:07:51.740 --> 00:07:53.740

countless other galaxies towards it at

189

00:07:53.740 --> 00:07:56.510

incredible speeds. The the problem is we

190

00:07:56.510 --> 00:07:59.150

can't observe it directly because it's hidden

191

00:07:59.150 --> 00:08:02.070

behind the zone of avoidance, the dusty

192

00:08:02.070 --> 00:08:04.350

star filled plane of our own galaxy.

193

00:08:04.830 --> 00:08:07.750

Anna: It's a mind boggling concept, like a

194

00:08:07.750 --> 00:08:10.310

hidden cosmic behemoth shaping the

195

00:08:10.310 --> 00:08:12.990

structure of our local universe. And

196

00:08:12.990 --> 00:08:15.830

speaking of strange observations, we have to

197

00:08:15.830 --> 00:08:18.230

talk about Tabby's star. Also known as

198

00:08:18.230 --> 00:08:18.910

KIC

199

00:08:19.230 --> 00:08:21.790

846-2852.

200

00:08:22.570 --> 00:08:24.810

This star exhibits bizarre and

201

00:08:24.890 --> 00:08:27.890

extreme dips in its brightness. We're not

202

00:08:27.890 --> 00:08:30.850

talking about the tiny regular dimming of a

203

00:08:30.850 --> 00:08:33.330

transiting exoplanet. These are

204

00:08:33.330 --> 00:08:36.250

massive irregular drops at one

205

00:08:36.250 --> 00:08:39.050

point blocking over 20% of the

206

00:08:39.050 --> 00:08:39.690

starlight.

207

00:08:40.090 --> 00:08:42.250

Avery: That's the star that famously led to

208

00:08:42.250 --> 00:08:45.050

speculation about alien megastructures

209

00:08:45.130 --> 00:08:47.850

like a Dyson swarm. While that's an exciting

210

00:08:47.850 --> 00:08:50.090

thought, the more plausible, though still

211

00:08:50.090 --> 00:08:52.940

unconfirmed explanation is is a vast

212

00:08:52.940 --> 00:08:55.780

uneven ring of cosmic dust orbiting the

213

00:08:55.780 --> 00:08:58.660

star. But the irregular nature of the dimming

214

00:08:58.660 --> 00:09:00.940

events makes it a persistent m and unique

215

00:09:00.940 --> 00:09:03.740

puzzle that defies easy explanation.

216

00:09:04.540 --> 00:09:07.020

Anna: It's a perfect example of how one

217

00:09:07.180 --> 00:09:09.900

strange object can challenge our assumptions.

218

00:09:10.460 --> 00:09:13.100

Then there's the other side of the dark coin.

219

00:09:13.420 --> 00:09:16.380

Dark energy. We discussed dark matter,

220

00:09:16.540 --> 00:09:19.500

the invisible glue holding galaxies together.

221

00:09:20.270 --> 00:09:22.750

Dark energy is its antithesis,

222

00:09:23.070 --> 00:09:25.470

a mysterious, repulsive force

223

00:09:25.710 --> 00:09:28.270

causing the expansion of the universe to

224

00:09:28.270 --> 00:09:30.870

accelerate. It's believed to account for

225

00:09:30.870 --> 00:09:33.710

nearly 70% of the universe's total

226

00:09:33.710 --> 00:09:36.670

energy density. And we have almost no

227

00:09:36.670 --> 00:09:37.870

idea what it is.

228

00:09:38.510 --> 00:09:41.350

Avery: So, to recap, about 25%

229

00:09:41.350 --> 00:09:43.910

of the universe is dark matter, which we

230

00:09:43.910 --> 00:09:46.900

can't see, and about 70 70% is

231

00:09:46.900 --> 00:09:49.620

dark energy, which we can't explain.

232

00:09:50.100 --> 00:09:52.780

That means all the stars, planets, and

233

00:09:52.780 --> 00:09:55.220

galaxies, everything we've ever observed,

234

00:09:55.460 --> 00:09:58.420

make up less than 5% of the cosmos.

235

00:09:58.740 --> 00:10:01.459

It's an incredibly humbling realization and

236

00:10:01.459 --> 00:10:03.460

drives home how much is left to discover.

237

00:10:04.260 --> 00:10:07.180

Anna: Absolutely. And perhaps the most profound

238

00:10:07.180 --> 00:10:09.940

mystery is one that strikes at the heart

239

00:10:09.940 --> 00:10:12.710

of physics itself. The black hole

240

00:10:12.790 --> 00:10:15.270

information paradox. General

241

00:10:15.350 --> 00:10:18.110

relativity suggests that information that

242

00:10:18.110 --> 00:10:21.030

falls into a black hole is gone forever,

243

00:10:21.430 --> 00:10:24.390

completely erased from the universe. However,

244

00:10:24.630 --> 00:10:27.510

a fundamental law of quantum mechanics

245

00:10:27.910 --> 00:10:30.670

states that information can never truly be

246

00:10:30.670 --> 00:10:31.270

destroyed.

247

00:10:31.910 --> 00:10:34.510

Avery: This creates a fundamental conflict between

248

00:10:34.510 --> 00:10:36.670

our two best theories describing the

249

00:10:36.670 --> 00:10:39.590

universe. To solve it, physicists may need a

250

00:10:39.590 --> 00:10:42.190

unified theory of quantum gravity, one that

251

00:10:42.190 --> 00:10:44.670

can explain both the macroscopic world of

252

00:10:44.670 --> 00:10:47.310

gravity and the microscopic world of

253

00:10:47.310 --> 00:10:50.030

quantum particles. Finding that solution

254

00:10:50.030 --> 00:10:52.590

could represent the single greatest leap in

255

00:10:52.590 --> 00:10:54.150

our understanding of reality.

256

00:10:54.870 --> 00:10:57.590

Anna: It's incredible. These puzzles,

257

00:10:57.590 --> 00:11:00.070

from cosmic structures to fundamental

258

00:11:00.070 --> 00:11:02.800

paradoxes, are, the driving force behind

259

00:11:02.880 --> 00:11:05.820

modern astronomy. They ensure that for

260

00:11:05.820 --> 00:11:08.620

every discovery we make, an even more

261

00:11:08.620 --> 00:11:11.300

fascinating question is waiting just beyond

262

00:11:11.300 --> 00:11:14.300

the horizon. And that's a perfect note

263

00:11:14.300 --> 00:11:17.140

to end on. It's a reminder of just how

264

00:11:17.140 --> 00:11:18.740

much there is still to explore.

265

00:11:19.460 --> 00:11:21.300

Avery: That's all the time we have for today's

266

00:11:21.300 --> 00:11:23.580

Astronomy Daily. We hope you enjoyed our

267

00:11:23.580 --> 00:11:25.940

journey through the latest in space news and

268

00:11:26.020 --> 00:11:28.820

cosmic mysteries. Join us next time as we

269

00:11:28.820 --> 00:11:31.460

continue to explore the universe. I'm Avery.

270

00:11:31.620 --> 00:11:34.460

Anna: And I'm Anna. Until then, keep looking

271

00:11:34.460 --> 00:11:34.820

up.

0

00:00:00.400 --> 00:00:03.400

Avery: Welcome to Astronomy Daily, the podcast that

1

00:00:03.400 --> 00:00:05.600

brings you the latest news from across the

2

00:00:05.600 --> 00:00:08.400

cosmos, as we like to say. Give us 10

3

00:00:08.400 --> 00:00:11.320

minutes and we'll give you the universe. I'm

4

00:00:11.320 --> 00:00:12.000

Avery.

5

00:00:12.240 --> 00:00:14.960

Anna: And I'm Anna. It's great to have you with us.

6

00:00:15.200 --> 00:00:17.680

We've got a packed show for you again today

7

00:00:17.920 --> 00:00:20.680

covering everything from historic launch pads

8

00:00:20.680 --> 00:00:23.480

being retired to incredible new discoveries

9

00:00:23.480 --> 00:00:25.520

by the James Webb Space Telescope.

10

00:00:26.040 --> 00:00:27.670

Avery: That's right, Anna. we'll be looking at

11

00:00:27.670 --> 00:00:29.950

China's progress on reusable rockets,

12

00:00:30.110 --> 00:00:32.870

Australia's orbital ambitions, and we'll end

13

00:00:32.870 --> 00:00:35.030

the show with a deep dive into some of the

14

00:00:35.030 --> 00:00:37.150

biggest unsolved mysteries in space.

15

00:00:37.870 --> 00:00:40.670

Anna: So let's get started. Avery. First

16

00:00:40.670 --> 00:00:43.310

up is an end of an era for SpaceX.

17

00:00:43.870 --> 00:00:46.190

Avery: It certainly is. SpaceX is

18

00:00:46.190 --> 00:00:48.870

decommissioning its original Starship launch

19

00:00:48.870 --> 00:00:51.070

pad, known as Pad 1, or

20

00:00:51.150 --> 00:00:54.110

Suborbital Pad A, at its Starbase

21

00:00:54.110 --> 00:00:56.700

facility in Texas. And this pad was the

22

00:00:56.700 --> 00:00:58.780

workhorse for the early days of Starship

23

00:00:58.780 --> 00:01:01.140

development, seeing a total of 11

24

00:01:01.300 --> 00:01:01.940

flights.

25

00:01:02.180 --> 00:01:04.740

Anna: It's amazing to think about the history made

26

00:01:04.740 --> 00:01:07.500

there. This wasn't just a simple concrete

27

00:01:07.500 --> 00:01:10.140

slab. It went through some massive upgrades

28

00:01:10.140 --> 00:01:10.820

over the years.

29

00:01:11.060 --> 00:01:13.710

Avery: Absolutely. it was eventually equipped with a

30

00:01:13.710 --> 00:01:16.550

full launch tower, a water deluge system to

31

00:01:16.550 --> 00:01:18.710

protect the pad from the intense heat of

32

00:01:18.710 --> 00:01:21.470

liftoff, and even the arms designed to catch

33

00:01:21.470 --> 00:01:24.150

and support the massive super heavy boosters

34

00:01:24.150 --> 00:01:24.870

for reuse.

35

00:01:25.220 --> 00:01:27.780

Anna: A true testament to their iterative design

36

00:01:27.860 --> 00:01:30.700

process. While it's sad to see it go, I

37

00:01:30.700 --> 00:01:32.660

imagine they need the space for the next

38

00:01:32.660 --> 00:01:33.540

phase of development.

39

00:01:33.940 --> 00:01:36.540

Avery: Exactly. They're moving on to bigger and

40

00:01:36.540 --> 00:01:38.500

better things with their new orbital launch

41

00:01:38.500 --> 00:01:41.020

site. But Pad one will always be remembered

42

00:01:41.020 --> 00:01:42.980

as where Starship learned to fly.

43

00:01:43.620 --> 00:01:46.540

Anna: Speaking of reusable rockets, SpaceX

44

00:01:46.540 --> 00:01:48.620

is getting some serious competition from M.

45

00:01:48.660 --> 00:01:51.500

China. The Chinese company Landspace

46

00:01:51.500 --> 00:01:53.460

has been making some impressive strides.

47

00:01:54.110 --> 00:01:56.870

Avery: They have. They're developing the Zhuque

48

00:01:56.870 --> 00:01:59.790

3 Rocket, which looks remarkably similar to

49

00:01:59.790 --> 00:02:02.790

Starship. It's a stainless steel, methane

50

00:02:02.790 --> 00:02:05.470

fueled, reusable launch vehicle. And they

51

00:02:05.470 --> 00:02:06.910

just hit a major milestone.

52

00:02:07.070 --> 00:02:09.909

Anna: The static fire test. Right. That's a

53

00:02:09.909 --> 00:02:10.670

crucial step.

54

00:02:10.990 --> 00:02:13.590

Avery: Right. They successfully completed a

55

00:02:13.590 --> 00:02:15.670

static fire test of the first stage

56

00:02:15.670 --> 00:02:17.990

prototype. This is where they fire up the

57

00:02:17.990 --> 00:02:20.190

engines while the rocket is securely bolted

58

00:02:20.190 --> 00:02:22.510

to the ground to testing the entire system

59

00:02:22.510 --> 00:02:24.070

under flight light conditions.

60

00:02:24.550 --> 00:02:25.830

Anna: So what's next for them?

61

00:02:26.150 --> 00:02:28.630

Avery: Landspace is aiming for its first orbital

62

00:02:28.630 --> 00:02:31.630

flight test in late 2025. This

63

00:02:31.630 --> 00:02:33.670

is all part of a much larger ambition for

64

00:02:33.670 --> 00:02:36.030

China, which is heavily investing in building

65

00:02:36.030 --> 00:02:38.830

its own space infrastructure, including a

66

00:02:38.830 --> 00:02:41.430

satellite constellation similar to Starlink.

67

00:02:41.670 --> 00:02:43.710

The pace of their development is really

68

00:02:43.710 --> 00:02:44.470

Something to watch.

69

00:02:44.790 --> 00:02:47.350

Anna: From engineering marvels on Earth to

70

00:02:47.350 --> 00:02:50.070

incredible discoveries far from home, the

71

00:02:50.070 --> 00:02:52.470

James Webb Space Telescope has deep done it

72

00:02:52.470 --> 00:02:55.070

again. This time giving us a peek into how

73

00:02:55.070 --> 00:02:56.390

moons might be born.

74

00:02:56.550 --> 00:02:59.310

Avery: This story is fascinating. Webb has

75

00:02:59.310 --> 00:03:01.870

observed a disk of material swirling around

76

00:03:01.870 --> 00:03:04.870

an exoplanet about 600 light years away.

77

00:03:05.270 --> 00:03:08.029

Anna: And this isn't just any disk. It's

78

00:03:08.029 --> 00:03:10.630

what's known as a circumplanetary disk.

79

00:03:10.630 --> 00:03:13.030

And it's the first time we've seen one that

80

00:03:13.030 --> 00:03:15.990

is rich in carbon. Scientists believe

81

00:03:16.070 --> 00:03:18.550

these disks are the birthplaces of moons,

82

00:03:18.790 --> 00:03:20.470

or exomoons in this case.

83

00:03:21.090 --> 00:03:23.380

Avery: So we're essentially watching a, moon system

84

00:03:23.380 --> 00:03:26.300

in the process of forming. Much like how the

85

00:03:26.300 --> 00:03:28.340

moons of Jupiter or Saturn might have formed

86

00:03:28.340 --> 00:03:30.300

in our own solar system billions of years

87

00:03:30.300 --> 00:03:30.580

ago.

88

00:03:30.980 --> 00:03:33.940

Anna: Precisely. The finding provides a, ah, rare

89

00:03:34.100 --> 00:03:36.380

real time look at the building blocks of

90

00:03:36.380 --> 00:03:39.060

moons and helps us understand the conditions

91

00:03:39.060 --> 00:03:41.980

under which they form. The power of the Webb

92

00:03:41.980 --> 00:03:44.540

telescope continues to unlock secrets of

93

00:03:44.540 --> 00:03:47.260

planetary formation that were completely out

94

00:03:47.260 --> 00:03:48.820

of reach just a few years ago.

95

00:03:49.350 --> 00:03:51.510

Avery: Lets bring our focus back to Earth now,

96

00:03:51.750 --> 00:03:54.350

specifically to Australia. The Australian

97

00:03:54.350 --> 00:03:57.070

rocket company Gilmour Space is gearing up

98

00:03:57.070 --> 00:03:59.110

for another shot at reaching orbit.

99

00:03:59.430 --> 00:04:01.870

Anna: Their first attempt didn't quite make it, did

100

00:04:01.870 --> 00:04:02.150

it?

101

00:04:02.470 --> 00:04:05.430

Avery: Unfortunately not. The flight was terminated

102

00:04:05.430 --> 00:04:08.070

shortly after liftoff due to an anomaly.

103

00:04:08.310 --> 00:04:11.150

But in the world of spaceflight, failure

104

00:04:11.150 --> 00:04:13.910

is often part of the process. The company

105

00:04:13.910 --> 00:04:16.630

has analyzed the data and is now targeting

106

00:04:16.630 --> 00:04:19.270

2026 for its second orbital

107

00:04:19.270 --> 00:04:19.670

attempt.

108

00:04:20.390 --> 00:04:23.190

Anna: It's a resilient industry. What does

109

00:04:23.190 --> 00:04:25.430

this mean for Australia's space program?

110

00:04:26.070 --> 00:04:28.870

Avery: It's a huge deal. A successful launch

111

00:04:28.870 --> 00:04:31.670

would make Australia the 12th country to

112

00:04:31.670 --> 00:04:34.590

reach orbit from its own soil. Gilmour

113

00:04:34.590 --> 00:04:36.710

Space remains optimistic and their

114

00:04:36.710 --> 00:04:39.230

determination is really fueling the growth of

115

00:04:39.230 --> 00:04:41.990

the nation's sovereign space industry. We'll

116

00:04:41.990 --> 00:04:43.750

be watching closely in 2026.

117

00:04:44.390 --> 00:04:47.330

Anna: All right, for our final segment, let's,

118

00:04:47.480 --> 00:04:50.440

let's venture into the unknown. Despite

119

00:04:50.600 --> 00:04:53.200

all our incredible technology and

120

00:04:53.200 --> 00:04:56.200

discoveries, space is still filled with

121

00:04:56.280 --> 00:04:59.160

profound mysteries that continue to puzzle

122

00:04:59.160 --> 00:04:59.720

scientists.

123

00:05:00.520 --> 00:05:03.160

Avery: My favorite kind of topic, where do we start?

124

00:05:03.800 --> 00:05:06.360

Anna: Let's start with the big one, the Hubble

125

00:05:06.360 --> 00:05:09.000

Tension. For years there's been a major

126

00:05:09.080 --> 00:05:11.960

disagreement on just how fast the universe

127

00:05:11.960 --> 00:05:14.720

is expanding. Measurements from the early

128

00:05:14.800 --> 00:05:17.320

universe, like the cosmic microwave

129

00:05:17.320 --> 00:05:20.120

background, give us one number. But

130

00:05:20.120 --> 00:05:23.040

measurements from the local modern universe

131

00:05:23.280 --> 00:05:26.120

using things like supernovae give us

132

00:05:26.120 --> 00:05:28.000

a different number faster.

133

00:05:28.800 --> 00:05:31.160

Avery: And the fact that they don't match suggests

134

00:05:31.160 --> 00:05:33.400

we might be missing something fundamental

135

00:05:33.400 --> 00:05:35.280

about the physics of the cosmos.

136

00:05:35.760 --> 00:05:38.240

Anna: Exactly. Next up,

137

00:05:38.400 --> 00:05:41.260

fast radio bursts or FRBs.

138

00:05:41.740 --> 00:05:43.820

These are incredibly powerful

139

00:05:44.060 --> 00:05:46.700

millisecond long bursts of radio Waves from

140

00:05:46.700 --> 00:05:49.380

deep space. We know they come from

141

00:05:49.380 --> 00:05:52.260

distant galaxies, but we have no idea

142

00:05:52.260 --> 00:05:54.900

what causes them. Theories range from

143

00:05:54.900 --> 00:05:57.340

magnetars to alien signals,

144

00:05:57.740 --> 00:05:59.660

but nothing fits all the data.

145

00:06:00.300 --> 00:06:02.230

Avery: A, true cosmic whodunnit.

146

00:06:02.630 --> 00:06:05.350

Anna: Then there's the giant elephant in the room.

147

00:06:05.930 --> 00:06:08.650

Dark matter. We see its gravitational

148

00:06:08.650 --> 00:06:11.290

effects everywhere. In the rotation of

149

00:06:11.290 --> 00:06:13.850

galaxies, in the bending of starlight.

150

00:06:14.170 --> 00:06:16.570

But we can't see the stuff itself.

151

00:06:17.050 --> 00:06:19.930

It makes up about 85% of the

152

00:06:19.930 --> 00:06:22.530

matter in the universe and we have no

153

00:06:22.530 --> 00:06:23.770

idea what it is.

154

00:06:24.410 --> 00:06:26.570

Avery: It's humbling to think that we've only ever

155

00:06:26.570 --> 00:06:29.210

observed a tiny fraction of what's actually

156

00:06:29.290 --> 00:06:29.930

out there.

157

00:06:30.250 --> 00:06:33.160

Anna: It really is. Lets touch on

158

00:06:33.160 --> 00:06:35.880

a few more strange ones. We recently

159

00:06:35.960 --> 00:06:38.960

detected the second longest gamma ray burst

160

00:06:38.960 --> 00:06:41.960

ever seen. It lasted for over a thousand

161

00:06:42.040 --> 00:06:44.840

seconds. We think these bursts come

162

00:06:44.840 --> 00:06:47.480

from collapsing massive stars. But

163

00:06:47.559 --> 00:06:50.120

one lasting that long challenges our

164

00:06:50.120 --> 00:06:52.920

models. Wow. Then there's

165

00:06:52.920 --> 00:06:55.840

Hoag's object. A bizarre galaxy that looks

166

00:06:55.840 --> 00:06:58.680

like a perfect ring of young blue stars

167

00:06:58.840 --> 00:07:01.480

surrounding an older yellow nucleus

168

00:07:01.640 --> 00:07:04.580

with almost nothing in between. We

169

00:07:04.580 --> 00:07:05.940

don't know how it formed.

170

00:07:06.340 --> 00:07:08.180

Avery: That sounds like something out of science

171

00:07:08.180 --> 00:07:08.660

fiction.

172

00:07:09.300 --> 00:07:12.100

Anna: And another great mystery closer to home.

173

00:07:12.420 --> 00:07:15.380

The hunt for Planet nine. The strange

174

00:07:15.380 --> 00:07:18.060

clustered orbits of several objects in the

175

00:07:18.060 --> 00:07:20.860

outer solar system suggest there might be

176

00:07:20.860 --> 00:07:23.740

a massive undiscovered planet lurking

177

00:07:23.740 --> 00:07:26.260

out there, 10 times the mass of Earth.

178

00:07:26.660 --> 00:07:29.380

But despite years of searching, we haven't

179

00:07:29.380 --> 00:07:29.860

found it.

180

00:07:30.580 --> 00:07:32.980

Avery: These mysteries are what make astronomy so

181

00:07:32.980 --> 00:07:35.780

exciting. For every answer we find, we

182

00:07:35.780 --> 00:07:38.500

uncover 10 new questions. The list of

183

00:07:38.500 --> 00:07:40.980

cosmic conundrums is seemingly endless.

184

00:07:41.460 --> 00:07:44.220

Take the Great Attractor for instance. It's a

185

00:07:44.220 --> 00:07:47.180

massive gravitational anomaly located in the

186

00:07:47.180 --> 00:07:49.220

direction of the Hydra Centaurus

187

00:07:49.220 --> 00:07:51.740

supercluster, pulling our Milky Way and

188

00:07:51.740 --> 00:07:53.740

countless other galaxies towards it at

189

00:07:53.740 --> 00:07:56.510

incredible speeds. The the problem is we

190

00:07:56.510 --> 00:07:59.150

can't observe it directly because it's hidden

191

00:07:59.150 --> 00:08:02.070

behind the zone of avoidance, the dusty

192

00:08:02.070 --> 00:08:04.350

star filled plane of our own galaxy.

193

00:08:04.830 --> 00:08:07.750

Anna: It's a mind boggling concept, like a

194

00:08:07.750 --> 00:08:10.310

hidden cosmic behemoth shaping the

195

00:08:10.310 --> 00:08:12.990

structure of our local universe. And

196

00:08:12.990 --> 00:08:15.830

speaking of strange observations, we have to

197

00:08:15.830 --> 00:08:18.230

talk about Tabby's star. Also known as

198

00:08:18.230 --> 00:08:18.910

KIC

199

00:08:19.230 --> 00:08:21.790

846-2852.

200

00:08:22.570 --> 00:08:24.810

This star exhibits bizarre and

201

00:08:24.890 --> 00:08:27.890

extreme dips in its brightness. We're not

202

00:08:27.890 --> 00:08:30.850

talking about the tiny regular dimming of a

203

00:08:30.850 --> 00:08:33.330

transiting exoplanet. These are

204

00:08:33.330 --> 00:08:36.250

massive irregular drops at one

205

00:08:36.250 --> 00:08:39.050

point blocking over 20% of the

206

00:08:39.050 --> 00:08:39.690

starlight.

207

00:08:40.090 --> 00:08:42.250

Avery: That's the star that famously led to

208

00:08:42.250 --> 00:08:45.050

speculation about alien megastructures

209

00:08:45.130 --> 00:08:47.850

like a Dyson swarm. While that's an exciting

210

00:08:47.850 --> 00:08:50.090

thought, the more plausible, though still

211

00:08:50.090 --> 00:08:52.940

unconfirmed explanation is is a vast

212

00:08:52.940 --> 00:08:55.780

uneven ring of cosmic dust orbiting the

213

00:08:55.780 --> 00:08:58.660

star. But the irregular nature of the dimming

214

00:08:58.660 --> 00:09:00.940

events makes it a persistent m and unique

215

00:09:00.940 --> 00:09:03.740

puzzle that defies easy explanation.

216

00:09:04.540 --> 00:09:07.020

Anna: It's a perfect example of how one

217

00:09:07.180 --> 00:09:09.900

strange object can challenge our assumptions.

218

00:09:10.460 --> 00:09:13.100

Then there's the other side of the dark coin.

219

00:09:13.420 --> 00:09:16.380

Dark energy. We discussed dark matter,

220

00:09:16.540 --> 00:09:19.500

the invisible glue holding galaxies together.

221

00:09:20.270 --> 00:09:22.750

Dark energy is its antithesis,

222

00:09:23.070 --> 00:09:25.470

a mysterious, repulsive force

223

00:09:25.710 --> 00:09:28.270

causing the expansion of the universe to

224

00:09:28.270 --> 00:09:30.870

accelerate. It's believed to account for

225

00:09:30.870 --> 00:09:33.710

nearly 70% of the universe's total

226

00:09:33.710 --> 00:09:36.670

energy density. And we have almost no

227

00:09:36.670 --> 00:09:37.870

idea what it is.

228

00:09:38.510 --> 00:09:41.350

Avery: So, to recap, about 25%

229

00:09:41.350 --> 00:09:43.910

of the universe is dark matter, which we

230

00:09:43.910 --> 00:09:46.900

can't see, and about 70 70% is

231

00:09:46.900 --> 00:09:49.620

dark energy, which we can't explain.

232

00:09:50.100 --> 00:09:52.780

That means all the stars, planets, and

233

00:09:52.780 --> 00:09:55.220

galaxies, everything we've ever observed,

234

00:09:55.460 --> 00:09:58.420

make up less than 5% of the cosmos.

235

00:09:58.740 --> 00:10:01.459

It's an incredibly humbling realization and

236

00:10:01.459 --> 00:10:03.460

drives home how much is left to discover.

237

00:10:04.260 --> 00:10:07.180

Anna: Absolutely. And perhaps the most profound

238

00:10:07.180 --> 00:10:09.940

mystery is one that strikes at the heart

239

00:10:09.940 --> 00:10:12.710

of physics itself. The black hole

240

00:10:12.790 --> 00:10:15.270

information paradox. General

241

00:10:15.350 --> 00:10:18.110

relativity suggests that information that

242

00:10:18.110 --> 00:10:21.030

falls into a black hole is gone forever,

243

00:10:21.430 --> 00:10:24.390

completely erased from the universe. However,

244

00:10:24.630 --> 00:10:27.510

a fundamental law of quantum mechanics

245

00:10:27.910 --> 00:10:30.670

states that information can never truly be

246

00:10:30.670 --> 00:10:31.270

destroyed.

247

00:10:31.910 --> 00:10:34.510

Avery: This creates a fundamental conflict between

248

00:10:34.510 --> 00:10:36.670

our two best theories describing the

249

00:10:36.670 --> 00:10:39.590

universe. To solve it, physicists may need a

250

00:10:39.590 --> 00:10:42.190

unified theory of quantum gravity, one that

251

00:10:42.190 --> 00:10:44.670

can explain both the macroscopic world of

252

00:10:44.670 --> 00:10:47.310

gravity and the microscopic world of

253

00:10:47.310 --> 00:10:50.030

quantum particles. Finding that solution

254

00:10:50.030 --> 00:10:52.590

could represent the single greatest leap in

255

00:10:52.590 --> 00:10:54.150

our understanding of reality.

256

00:10:54.870 --> 00:10:57.590

Anna: It's incredible. These puzzles,

257

00:10:57.590 --> 00:11:00.070

from cosmic structures to fundamental

258

00:11:00.070 --> 00:11:02.800

paradoxes, are, the driving force behind

259

00:11:02.880 --> 00:11:05.820

modern astronomy. They ensure that for

260

00:11:05.820 --> 00:11:08.620

every discovery we make, an even more

261

00:11:08.620 --> 00:11:11.300

fascinating question is waiting just beyond

262

00:11:11.300 --> 00:11:14.300

the horizon. And that's a perfect note

263

00:11:14.300 --> 00:11:17.140

to end on. It's a reminder of just how

264

00:11:17.140 --> 00:11:18.740

much there is still to explore.

265

00:11:19.460 --> 00:11:21.300

Avery: That's all the time we have for today's

266

00:11:21.300 --> 00:11:23.580

Astronomy Daily. We hope you enjoyed our

267

00:11:23.580 --> 00:11:25.940

journey through the latest in space news and

268

00:11:26.020 --> 00:11:28.820

cosmic mysteries. Join us next time as we

269

00:11:28.820 --> 00:11:31.460

continue to explore the universe. I'm Avery.

270

00:11:31.620 --> 00:11:34.460

Anna: And I'm Anna. Until then, keep looking

271

00:11:34.460 --> 00:11:34.820

up.