Street Food and Public Markets in New Orleans

New Orleans is known for its unique cuisine that blends and highlights the many cultural roots of the city and its residents. The history of food distribution in New Orleans is just as unique within the American landscape, relying heavily on public food systems, both street vendors and municipally-run public markets. Joining me in this episode is Dr. Ashley Rose Young, a curator and public historian who serves as the American History Curator in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress and is a Smithsonian Research Associate. Her book, Nourishing Networks: The Public Culture of Food in New Orleans has just been published.

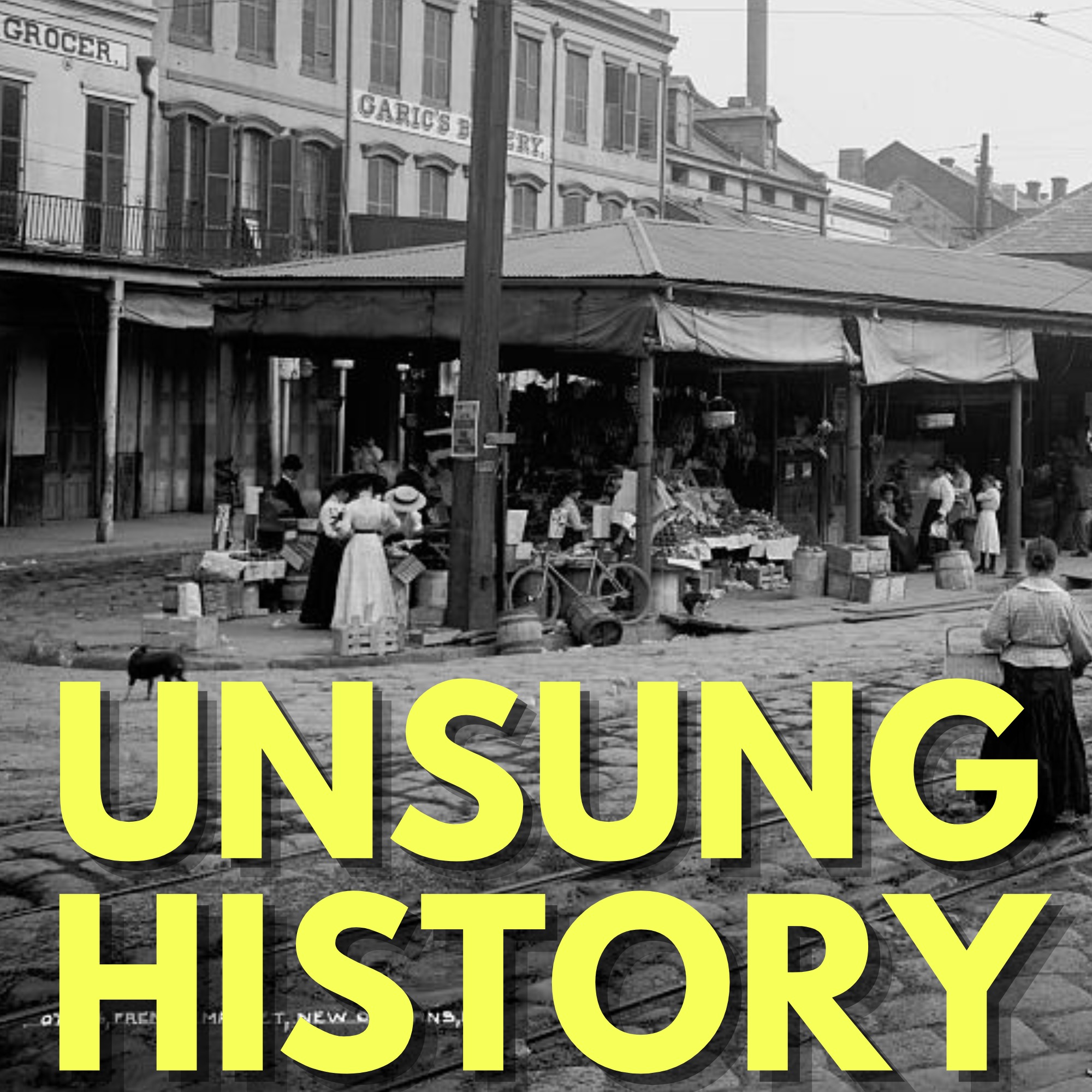

Our theme song is Frogs Legs Rag, composed by James Scott and performed by Kevin MacLeod, licensed under Creative Commons. The mid-episode music is “On my way to New Orleans,” composed by Albert Von Tilzer with lyrics by Ballard MacDonald; this performance was sung by George O’Connor on February 10, 1915, in New York, and is in the public domain and available via the Library of Congress National Jukebox. The episode image is: “French Market, New Orleans, La.,” Detroit Publishing Company, 1910; there are no known restrictions on publication, and the image is accessible via the Library of Congress.

Additional sources:

- “New Orleans History 101: A beginner’s guide to understanding the Crescent City,” by Historic New Orleans Collection Visitor Services Staff, January 21, 2022.

- “Timeline: New Orleans,” PBS American Experience.

- “New Orleans Then and Now: The French Market,” by Ellen Terrell, Library of Congress Blog, July 12, 2018.

- “The Native Roots of the French Market,”by Kalie Rhodes, New Orleans Historical: A project by The Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at the University of New Orleans, February 11, 2021.

- “200 Years of Commerce, Community & Culture,” French Market District.

- “New Orleans Street Vendors: A long history of African American entrepreneurship,” by Zella Palmer, 64 Parishes, December 1, 2019.

Advertising Inquiries: https://redcircle.com/brands

Kelly Therese Pollock 0:00

This is Unsung History, the podcast where we discuss people and events in American history that haven't always received a lot of attention. I'm your host, Kelly Therese Pollock. I'll start each episode with a brief introduction to the topic, and then talk to someone who knows a lot more than I do. Be sure to subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app so you never miss an episode, and please tell your friends, family, neighbors, colleagues, maybe even strangers, to listen too. The unique cuisine of New Orleans reflects the city's multicultural history. The French founded the city in 1718, on a site where multiple tribes of Native Americans had long gathered for trade and diplomacy. By 1723, New Orleans was the capital of France's Louisiana Colony. Four decades later, though, New Orleans was part of the territory that Spain acquired from France at the end of the Seven Years' War. France briefly reacquired New Orleans from Spain in 1800, but the United States purchased the Louisiana Territory from France a few years later, in 1803, for around $15 million. The first enslaved Africans were brought to the city by the French in 1719, a practice that continued through the Spanish rule of the city. By 1803, enslaved people made up over 1/3 of the population of New Orleans, bringing their own food culture to the city. New Orleans also had a large population of free Black people, beginning early in the French period and continuing through the resettlement of more than 3000 free people of color from Haiti, early in the American period. Prior to the Civil War, New Orleans had more free Black people than any other city in the Deep South. In the city's French period, Indigenous and Black vendors sold food in the city with few regulations. But when the Spanish took over, they created all kinds of laws related to selling food, including where, when and to whom, vendors could sell. In 1770, the Spanish created an open air market physically located near the government's administrative headquarters. Two commissioners regulated the sale of food in the city, their services paid for by vendor licenses and taxes on the sale of food and drink. In 1791, the city government built a covered market at the location of what is now the French Market. They remodeled and rebuilt the market throughout the remaining Spanish period. After New Orleans became a US territory, the city government continued to regulate the market, for instance, limiting the hours when butchers could sell their meat and giving preference to purveyors of meat and vegetable over those of dry goods. Not all vendors were found in the market, though. The city continued to issue licenses for itinerant vendors, although they too had regulations they were supposed to follow. In practice, the paper license system was difficult to enforce, and many people vended without a license. Black vendors, especially those outside of the marketplace, were susceptible to harassment in the wake of the 1806 Code Noir, which allowed anyone to stop enslaved vendors selling fresh food, and demand to see their vendor license. If the vendor couldn't show the license, the person who had asked to see it could be rewarded with either the goods they were selling or $2 from the enslaver. For three decades, the French Market was the only public market in the New Orleans area. But as the city's population grew rapidly, local officials realized that they needed to build more markets or risk the itinerant vendors becoming increasingly important to the local food economy. 14 neighborhood markets were approved between 1822 and 1860, starting with the St. Mary's Market, just over a mile from the French Market, built in the American sector of town. The construction of St. Mary's Market cost $22,000 for the 165 foot long by 42 foot wide structure, with a wood frame and a tiled interior. In some cases, public markets were built in neighborhoods that hadn't yet boomed. The construction of the market itself drove population growth and the development of a nearby commercial sector. After the Civil War, during Reconstruction, the Louisiana State Legislature passed a law permitting the operation of private food markets in New Orleans, which, unlike the public markets, could be open, "at all proper hours of the day." By 1874, there were more than 1374 grocery stores in New Orleans, and by law, they could all sell fresh food. That year, though, the state legislature responded to pressure from public market vendors, and passed a law that said that private markets could not operate within 12 blocks of a public market. Given the number of public markets in the city, that effectively outlawed the private markets. Over time, laws would change the distance of those restrictions, but the city government continued to prioritize the profitability of the public markets, even as they failed to maintain the facilities. By the late 1890s, the poor conditions were driving vendors away from the public markets, and the markets were bringing in only a fraction of the profits that they had at their peak. Responding to public health complaints, the city made minor improvements and renovations, but the problems continued. Finally, in the 1930s, with funding from the Public Works Administration and the Works Progress Administration, the city completely overhauled the public markets, with some of them getting complete rebuilds. Despite the newly clean and modern markets, though, the time of public markets had passed. As supermarkets popped up around the country, New Orleanians were no longer satisfied with their options in the public markets, and in 1945, the 14 remaining public markets operated at an overall loss. Over the next few years, the city began to sell off the structures with the last neighborhood public market structure auctioned off in 1958. The French Market remains to this day, though, instead of butcher stalls, you will find vendors selling jewelry and souvenirs alongside restaurants serving local cuisine. Joining me in this episode is Dr. Ashley Rose Young, a curator and public historian who serves as the American History Curator in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress, and who is a Smithsonian Research Associate. Her book, "Nourishing Networks: The Public Culture of Food in New Orleans," has just been published.

Kelly Therese Pollock 9:15

Hi, Ashley. Welcome back to Unsung History.

Ashley Rose Young 9:19

Thank you for having me. I'm so thrilled to be here today.

Kelly Therese Pollock 9:23

I really enjoyed your book. You've been working on this project a long time. I want to hear about what got you interested in it and kept you interested in it,

Ashley Rose Young 9:31

Of course. So imagine a young me in undergrad. I just became a history major, and I was on the lookout for topics for my senior thesis. And I so happened to have an internship at the Southern Food and Beverage Museum in New Orleans, Louisiana. And Liz Williams, who's the founder of that museum and my long, long time mentor, introduced me to Creole cuisine, and I, I was just, I mean, I couldn't get enough of the history. I'd always had an interest in New Orleans because I had studied French in elementary and middle school and high school, even in college as well, and we would celebrate Mardi Gras and learn about Creole culture. But I really didn't know that much about it, until this internship, and I started reading these historic cookbooks, and I was fascinated by the introductions to these cookbooks, how they described the creation of Creole cuisine, how they narrated the mythology around the different communities who contributed to one of the most iconic cuisines in the United States. And I just thought, I have to write my senior thesis on this. And that led to immediately going into a PhD, an MA, Ph D program. And then, you know, the journey continues and 15 plus years later, I'm actually holding my book today, which is beyond thrilling. It's like my first child, right? And yeah, that that's the beginning. It was just just an internship, but not just any internship, it was life changing.

Kelly Therese Pollock 11:19

The people that you're writing about are largely marginalized in society. These are not the kind of people who are leaving extensive archives. What are the kinds of sources that you looked at, and what are maybe some of the limitations of what we can learn from the sources?

Ashley Rose Young 11:37

That is a great question, and along this journey, I often ask myself, "Why? Why did I choose this topic?" It's really hard to find the answers to the questions that I have, but I think that's the kind of historian I am. I'm really drawn to stories that are not easily told, stories that require a bit of struggle and perseverance to share with the world. And you know, I will talk a little bit more about those historic cookbooks that I mentioned that I first encountered during that internship. And there was often reference to street vendors or African American individuals in the New Orleans community who were preparing classic Creole treats like pralines or making these staple dishes like gumbo. And I wanted to know more about these people, who they were, where they came from, how they contributed to and really shaped the trajectory of Creole cuisine. And so that's when I started looking for evidence, more evidence than just the narratives in these cookbooks, because that's where it all started. It was the stories in the cookbooks and how you have this narrative of the mingling of European, West African, Caribbean and Indigenous influences, right food cultures coming together in New Orleans and its surrounding area, but there was often, and this is characteristic of the time, a focus on the European influence. Many New Orleanians at the time were very proud of their French ancestry, their Spanish ancestry, these connections to Europe and to haute cuisine. I mean, around 1900 when these cookbooks were being published, French cuisine was the standard, as it is, really still to this day, of fine dining. And for New Orleans, which at one point in time, was a French colony, and then was part of, you know, a Spanish empire as well, there was pride in that European culinary tradition. But I wanted to see beyond that. I wanted to know about the people who were actually preparing the food, not only in the homes of wealthy individuals, whether as enslaved laborers or working in the domestic service industry. But I wanted to know about these people who were vending gumbo on the city streets, who were, you know, had found a space near the French Market, or who had set up a temporary stand or stall and were selling these prepared foods, like, who, who are they? And can we see them differently than just these sort of caricatures that are that are so often found in these cookbooks published 1885 through, you know, 1915, 1920s, and so on. And so I started looking at the local newspapers, and I was looking for references to pralines, to gumbo, to the French Market. And I started seeing these descriptions, more detailed about these individuals who are actually known for making a specific kind of gumbo, who were known for being the best coffee vendors in the city. And there were profiles of these individuals in the local papers. One of them is named Rose Nicaud. She was previously enslaved, but by vending coffee, she was able to earn a certain amount of money over many, many years. And this was common practice in New Orleans and other places in the antebellum south for an enslaved person to keep part of, but not all of the profits of the sale that they were making in the market. And really they were representing the business of their enslaver. But as these entrepreneurs themselves, they were able to keep a portion. And over time, some of them, not most of them were not able to but, but some were able to actually purchase their own freedom to self manumit through the sale of coffee or through pralines. And they became fairly famous figures. If you were successful enough as a business person to accumulate enough funds to purchase your own freedom, you are a known entity in the city. And so we have these articles that go into a little bit more depth about the lives of people like Rose Nicaud, for example, who had this very famous coffee stand in the French Market. She was known for having these beautiful copper coffee kettles where she was making the coffee right there in a traditional Creole style. And, you know, people came to the city, writers and tourists, and they went to her stand. They went to experience this very visceral, tangible, sensory moment by drinking her coffee, and then they would write about her, either publishing articles in the local paper or writing about her in their travel journals. And so that's another way that we start to get at some of these vendors, is through the stories of of people who found their their enterprise captivating and interesting, kind of similar to the foodie moments that we have in the 21st Century. It's a pilgrimage almost to go to certain bakeries or certain street food stalls or restaurants, because you've heard of the reputation, the stellar reputation, of these places, and you want to go experience that yourself. And so there was elements of this tourism culture, say, in the 1880s and 1890s. New Orleans was really trying to build itself back up after the Civil War and after reconstruction, and it really made this conscious effort as a city to attract tourists down to the south, down to the city that was seen as the Paris of America. And so much of that kind of foreignness or intrigue was tied to the city's food culture, and this melange, this Creole culture that was fairly unique to the city of New Orleans. So those are just some of the ways that we get at the stories. But of course, census records are key. Looking at records, notarial records are important, as are records from local trials in cases where a vendor might be speaking about their experience, their lived experience, just vending food every day, whether it's prepared or whether it's fresh food, like produce, and there might have been a crime or someone might have stolen from them, and they were testifying and sharing a bit about their lives. That's another way that we can get at some of these stories. But I do find that travel narratives in the newspapers were particularly helpful in kind of building out a more substantial image of who these these vendors were.

Kelly Therese Pollock 18:32

As you were talking about tourism, you said, you know, New Orleans was trying to bring people in. The city was thinking about its image and how it was selling itself. And in many ways, this story is a story of public policy just as much as a story of food. Could you talk about some of the ways that over the course of the time that you're writing about, that New Orleans and New Orleans government is thinking about vendors, is thinking about markets, is thinking about how best to both build up the city coffers but also protect customers.

Ashley Rose Young 19:06

That's a great question. And I will say, when I started off on this project, I was looking at those individual vendors, but as I continued to do more research, I began to see this larger context for who these vendors were and how they were operating their businesses, and that is the history of New Orleans public food culture. That's what I call it. This, this food culture that takes place not in brick and mortar stores, not in restaurants, but actually in the city streets, either by street vendors themselves or by vendors who are working in the open air or partially covered markets. And so this story of government regulation is a huge element of New Orleans food culture and its public food culture. And this is an age old tradition. It stems back to Europe and other places where there was a belief that the city government, or your local government, had a moral responsibility to help provide spaces where food could be sold economically and safely. This is this idea of a quote, unquote, moral economy. And that was brought to New Orleans in the colonial period, somewhat by the French, but honestly, it was the Spanish colonial government, known for their bureaucracy, known for their regulation. They came in and they said, "This city is like lawless, essentially. We need to create a little more structure for our citizens here, and for us, that means providing a central place where all food distribution is going to take place. We're going to sell our fresh meat here, seafood, produce, prepared goods, all in one space where we can monitor what's happening. We can make sure you're not price gouging the customers, and that you're serving them safe, non adulterated food." And again, this is a very deeply like this is a centuries old tradition, and it's honestly how many cities kind of form and grow is first you create a market, and then other businesses kind of form around that, because how can you have a city without being able to feed the population? And so what I found so interesting in New Orleans as we started to trace the growth of the city, because really, it was like a colonial outpost for so long, it was, it was small. I mean, around 1810, it was around 10,000 people or so, but by 1840 it was the second largest city in the United States. So it had huge growth in a period of just a few decades. But that growth was really spurred on in many ways by the creation of public markets. So New Orleans adopted a system of public markets that looked unlike any other in the United States. It actually adopted a culture like that of Paris, where you have the central market, which we know today as the French Market. But whenever a new neighborhood was built or was being planned, the first thing that a community would do was construct a neighborhood public market, and then you would have the other businesses come in. You would have residents starting to move into that neighborhood. And so we start to see that in New Orleans, like in Paris, public markets were literally the catalyst for growth for new neighborhoods. And this is kind of a theme that we really haven't studied too much in the history of urban studies in the United States. At least in New Orleans, the key role of food and of public markets, and these are, again, are city run markets, and they are meant to create a moral economy, so that everyone has access to these foods and that they can trust the foods are safe and affordable. I mean, what else could you could you ask for it? Well, I mean, many things like indoor plumbing, but you can't get too ahead of yourself. But throughout New Orleans history, the city just kept building more and more markets. It literally became a city of markets, with over 34 neighborhood markets operating in the city at its peak, and that's after 1900. But if you look at other American cities, by that time, most may have started with public markets, you know, one or two. But then by around the 1840s or 1850s, city governments were like, "You know what? This is too challenging. We're going to privatize these markets. We're going to let other people deal with them. And you know what, as a city government, we're going to we're going to back off." So in New York and Baltimore and these other areas, you see this mass adoption of the privatization of public markets. But that's not the case in New Orleans. And you might be asking, "Well, why is that?" And at first, I do believe it was part of that moral economy. There was a culture in New Orleans, a deep appreciation for these local retail centers. People were really prideful of their local public market. But then, unfortunately, things became really corrupt, and New Orleans city government was essentially, they basically forced people to buy all of their food in the public markets by making it essentially illegal for any green grocers to operate in the city. So in New York and Boston and other areas, you had your public market, say in 1820 but then you also had green grocers, you know, people who were selling fresh vegetables in a brick and mortar store, and they kind of coexisted together. But in New Orleans, not the case. Almost from the beginning, you had to vet, you had to vend, and you had to buy your goods at the public market. You know, at first that worked out because it was a good system. It did provide that important food for customers. But over time, customers started to look at other American cities and go, "Wait. They have choice. They can go to a grocery store, they can go somewhere else. They actually have the option to choose where they get their foods from." And similar, for vendors, they had a choice. They could go and operate a store if they wanted to, or they could vend in one of the public markets. But in New Orleans, that choice was eliminated, and eventually it was not really about moral economy. It was about the city government pulling money out of the public markets from all those vendor rental fees, and using those funds not to like, keep the public markets in good shape and keep everyone happy. They actually started using that money to build roads and build schools. And of course, these are, are civic projects that are that are good, but they stopped investing in the public markets. And so in the second half of the 19th century, you start to see these decrepit, you know, farm, these covered markets that are basically falling apart. They're infested with rats. You have yellow fever outbreak, you have bubonic plague outbreak. And people in New Orleans are just going nuts. They're like, we have no options. These places are not sanitary. We love them because we like the cultural elements and how they tailor, each vendor tailors their product to our individual community. But honestly, you really need to, like, repair these places, like we cannot shop here, and if the government is not going to repair them, you need to give us a free economy. We need to be able to go out and, you know, shop at a grocery store. You need to let grocery stores operate and sell fresh foods, because it was still illegal at that time. And so this was like a complicated back and forth for decades and decades. I mean, there was bubonic plague outbreak in the 1910s in New Orleans, and a lot of in large part because the city markets were very near the port, and you have trade coming through the port. And, you know, people think, oh, that's an old world disease. No, it was, it was here in New Orleans, just over 100 years ago. So there were many, many issues, so much back and forth. You know, customers are fighting the local government. Vendors are fighting the local government. And the city of New Orleans will not let go. They just they will not let go. They make some concessions in the 20th century, but really they are operating on the illegality of grocery stores. They depend on that for you know, well into the 1930s and it's really not till World War II that things open up, and actually the public markets closed down for the most part, and a free economy takes hold in New Orleans. But that has its own consequences too. But yeah, city regulation. It's a it's an ugly tale. It's it's rife with subversive behavior and protest and people illegally operating grocery stores and creating black markets. And it's very controversial and interesting, but really it comes down to the basics of people just want choice. They want a choice where they eat. They want a choice where they buy their foods. And similarly, if they're entrepreneurs, they want to have choice on where they vend.

Kelly Therese Pollock 28:28

Listeners may expect that a story like this, the things like smell and taste and things are important, but you also write a lot about sound, the sounds of vending. So I wonder if you could talk some about writing about that, but also like, how do we research that when some of what you're writing about is before the advent of recorded sounds?

Ashley Rose Young 28:48

I know, I know. I love the sound studies element in this work. And I think when I started thinking about food history, and I think when other people think about food history, they're imagining that the archive is going to tell them about taste, right, the taste of food, the textures of food, the smell of gumbos. I mean, Oh, the smell of baking bread. This is what you imagine you're going to come across. But by studying street vendors, what I found to be the most common sensory experience that was described in the archives is sound, and that is because of the advertising strategies of street vendors in New Orleans and in places across the globe. They are the you know, they are the creators of the advertising jingle. Street vendors are, because if you're operating a little stand on the street, or if you're in an overcrowded market, how do you catch the attention of passers by? You do it through song. And street vendors were incredibly creative with these songs. Some sang very melodic songs. Some improvised, and would kind of incorporate elements like, hey lady over there, and they might incorporate a reference to the clothing she's wearing, or, you know, use rhyme and popular tunes of the time any way, any way they could capture the attention of people, they would implement it. And they had fantastic street cries. They were so interesting and captivating that visitors to the city would often try to transpose the street vendor cries they were hearing onto paper. And some did this, you know, through musical notation. They actually would like record the melody using the notes we learned in school, and they would write the lyrics below. Others who may not have been able to transpose music that way, they would try to use hyphens and dashes and other things while they were writing out the words or the lyrics of the song, to try to capture the emphasis of particular vendors. And I'd be happy to sing an example of a vendor cry for you. And this is actually one about horseradish that the Smithsonian Folklife Center captured. And it was actually recorded on CD. You can listen to it today, but it's a little, a funny little song. Just imagine this cry ringing through the streets of New Orleans. "Horseradish. Horseradish. Good old Tom never lies. Grind your horseradish for your wives. Horseradish. Horseradish, horseradish." So that is an example. Now, not all of the street vendor cries were that melodic, but we just have so many examples of people, travelers like just totally enamored with the soundscape, and they're really funny. I mean, it's not just in New Orleans. You have examples in New York, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, these little ditties, these these cries. And I found them absolutely captivating. Some people found them charming in the ways that I did. But many local people in New Orleans also found them extremely annoying, because you can imagine having hundreds of vendors working in the city. Many of them started at the crack of dawn. And countless New Orleanians talk about waking up to the sound of the blackberry vendor, or waking up to the sound of, you know, the praline vendor, that these were the kind of natural alarm clocks for the city. But at some point, there were so many vendors singing and clashing with each other that there was just this, like, ungodly cacophony of sound. And it was just like, please, I just want some quiet. And all I can hear is this uproar from the French Market and the surrounding streets. So it kind of just shows you the different perspectives that one can have of sound at that time, and in New Orleans, you have to keep in mind that race and class certainly play into this ethnicity, where you have people who held great prejudice against recent immigrants or enslaved people or free people of color who saw their singing as grating or something that they didn't want to listen to, but certainly that was wrapped up in prejudices that individuals held of each other. And you know, in the late 19th century, for example, New Orleans had one of the largest Sicilian populations in the world, which really surprises people. They don't most people don't associate New Orleans with a strong Sicilian or Italian influence. But, you know, the French Quarter at the time was known as Little Palermo, and we have so many instances in the local paper where people are writing about the accented street cries of the Italian vendor selling fresh fish. And some of them are, are, you know, positive memories, but others are just saying, "Oh, these, these people are coming around, and they're waving their offensive, smelling fish in my window, and they're coming into my home and crying out about their wares." And, you know, this, this particular person felt that it was an invasion on their private property and and things like that. But certainly, again, it's wrapped up in these ideas of ethnicity and race and who should be able to navigate certain spaces in the city. But the brilliant thing about street food culture is that, you know, people are using public space. They're using sidewalks, they're using city parks, and they're kind of elbowing their own way into the local food economy because they could. This doesn't mean they weren't caught for doing so, or that the local government didn't try to suppress their efforts, but when you're constantly on the move as a street vendor, you're really hard to regulate, and so street food was a really natural starting point for people who were otherwise economically disenfranchised, who didn't have the right to vote. But everyone could, if they were savvy enough, navigate public spaces and get away with selling, even if they didn't have a license, even if they weren't selling legitimately. And these were people who were just trying to put food on the table for their families and, you know, scrape out a living for themselves. And you see time and time again, for example, with the Italian vendors who might have migrated in the late 19th century, you see that many of them went on to start their own little stalls in one of the local markets. Maybe then they went on to open up a little cafe or a restaurant, then to a macaroni factory. You see this kind of upward mobility for European migrants. But then when you're looking at the experiences of African American vendors, you see so often that they're not able to move far beyond street vending, that they're in the Jim Crow South. They were just not having access to they were they were barred from the banks, you know, the the lending practices. There were so many barriers in their way, and yet they still were able to in the ways that they could carve out spaces for themselves, at least within the street vending practice, although certainly we're not often able to climb the economic ladder like some of their peers in the food economy.

Kelly Therese Pollock 36:33

Let's jump ahead to the 21st Century. So things have kind of come full circle in certain ways. We now have farmers markets run by city governments, local governments all over the country, including in New Orleans. We've got food trucks everywhere. It's easier for me to get to a food truck for lunch than to a standing restaurant some days. And this episode is coming out on the eve of the New York City election, where one of the major candidates is proposing city run grocery stores. So could you talk a little bit about using the past and what we know about the past to think about the current day in the future?

Ashley Rose Young 37:08

Yes. So my hope with "Nourishing Networks" my book, was that public policymakers people really thinking about our modern food systems and all of the ways in which our food systems are broken. They're not serving our modern society in the way that they need to. I'm really hoping they can read this book and think fairly deeply about where we have come from and the lessons that we can learn from New Orleans and other cities. And not all of those lessons are positive. You know, some of those lessons are what not to do. But when I think about a city sponsored grocery store or the proposal for that, I immediately thought back on on this idea of moral economy that came out of Europe, and I think about New Orleans experiences having city regulated public markets, and and how that worked so well for so long, until the city government, in a very corrupt way, said, "Oh, well, no, we want these places just to be ways to fill our general coffers and then use that for other city projects." So when I think about what's happening in Louisiana today, or New Orleans, for example, you know, as of 2023, one in seven people and one in four children in Louisiana were struggling with hunger. It has a very high hunger rate and and we talk about today's food deserts. The term is complicated, and not everyone finds that to be the most appropriate term to describe communities that lack access to affordable, safe, culturally appropriate foods, but I do feel like there is a seed of opportunity in looking to the past, where, you know, today, it's not economically viable necessarily for a grocery store to come into an economically disadvantaged community. The way that our economic systems work, it's difficult for them to make a profit, right? So what is our alternative? You know, is this an opportunity to provide a city sponsored space, city regulated where it's going to have that affordable food, it's going to be employing local people? And I do think there's an opportunity there to look at the New Orleans model, where each neighborhood had these small scale markets. You know, they might have had 10 or 15 vendors that were trusted, that you knew you would go see them every day, and you actually built a substantial relationship with the people you were buying food from. And that's really what we're getting at in "Nourishing Networks." It's not just about access to food or the affordability. It's this idea that your vendors, the people you're buying from, actually care about who you are as a person. They actually have a relationship with you, and in turn, you have a relationship with them. And it builds trust. It builds a sense of community. You feel like, you know, like you're building something more than just buying food, and that's really hard to get in a modern grocery store today, and I say that my family operated gourmet grocery food stores in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, my hometown, for 70 years. We were a small scale operation, we were really dedicated to our local communities in building those relationships with our customers who knew us. You know, they saw me ringing up people the cash register when I was nine years old. And so I think that's a key element where it's bringing the humanity back into our food systems and getting to know the people, not just the people who grow your food, that's a huge movement with farmers markets, to know the people who grow your food. But also, I argue you need, you need to know the people who distribute the food as well. But the last point I want to make on that topic is the importance of retail inequality. So there's a great scholar who writes about this work, and his last name is Kolb, K, o, l, b, and he has done many studies on why certain initiatives to help ameliorate the effects of food deserts haven't worked. And he studied Greenville, for example, and there were efforts to bring in, you know, city sponsored grocery stores, or at least subsidize. And he interviewed the community members in these economically disadvantaged areas, and many of them were people of color. And they, you know, the people he interviewed said it's not just about having food that is cheap or affordable or even healthy. It's the fact that, like we are people, we deserve to have the same choices as community members two miles down the road or five miles down the road in a more economically advantaged area. We should be able to walk to our grocery store, to walk to these different retails operators who have all pulled out of our community because it's not economically advantageous to them. Like we just want to be treated as people as everyone else. And that's why I turned back to the New Orleans model, where every neighborhood had a public market, regardless if it was a historically Black community or a community of you know, where racial or economic backgrounds were diverse, everyone had access. They were all within all these public markets. The 30 plus public markets in New Orleans were all within about one mile of each other. So you could easily walk to them. They were there for everyone. There wasn't really this idea of, oh, this place has a better public market than our public market. People had retail equality in historic New Orleans. And I wonder if there's a way that we could bring that back to our modern society. But it's not. It's, I wish that were the you know, that's all we had to do, and that's the easy solution, if only. You know, I'm not a policymaker, but I do hope that current policymakers or politicians might find inspiration in these historic models to see where they did work and to again, recognize the humanity in all of us, that consumers want choice, and they want equal choice. They want the same options, options as anyone else, and I think that's a very understandable thing to desire. And again, I am sympathetic to the entrepreneurs themselves. My book is so much about entrepreneurs, and I come from an entrepreneurial family in the grocery store business of which I am so proud of, but it's a very complicated situation. But ultimately, I do see the value in city involvement, city government involvement in the in the retailing of food to help build that equality and and hopefully provide as much choice as possible to all consumers.

Kelly Therese Pollock 44:00

Could you tell the policymakers who may be listening and everyone else how they can get a copy of the book?

Ashley Rose Young 44:07

Of course. So you can find a copy of the book at your local bookstore. Or here in DC, you can always reach out to Politics and Prose or Lost City Books. And then, of course, if you're looking for, you know, something easily accessible online, it's available on amazon.com, on walmart.com. There's many different ways to find "Nourishing Networks," and I'm always happy to keep the conversation going. You can feel free to reach out to me on social media, and I'm at @AshleyRoseYoung, all one word, on basically all platforms.

Kelly Therese Pollock 44:41

Is there anything else you wanted to make sure we talked about?

Ashley Rose Young 44:45

I think the last thing I'd like to mention is to as much as I've talked about the complexities of the system and the hunger that people face today and faced in the past, I do want to honor, throughout time, the creativity of entrepreneurs and the resilience of street food vendors, many of whom have incredibly inspiring stories, which I have included in this book. I had mentioned Rose Nicaud before, but there are many other vendors who have these they're really just inspiring. You see these people facing so many barriers to entry, and yet they carved a space for themselves in the economy, and they made a name for themselves in really surprising ways. And I hope to honor that and again, to find the humanity in these experiences and to recognize around us the street vendors in major cities today in the United States. We still have a public food culture. It's not the same as it was, say, 100 years ago, but it is a derivation of that culture, and it's something to be proud of, but also something to be mindful of. How can we support and be respectful of small scale entrepreneurs who are again, just striving to put food on their tables, to make it in in our fast paced economy today, and get out there, get to know them. Human connection is key. And remember that food really is something that can connect us all, if only we take that kind of initial, I don't know if you'd say first bite, but if we take that first step or first bite to get to know each other.

Kelly Therese Pollock 46:26

Ashley, thank you so much for joining me today.

Ashley Rose Young 46:28

It was a pleasure. Thanks for having me.

Teddy 46:58

Thanks for listening to Unsung History. Please subscribe to Unsung History on your favorite podcasting app. You can find the sources used for this episode and a full episode transcript @UnsungHistoryPodcast.com. To the best of our knowledge, all audio and images used by Unsung History are in the public domain or are used with permission. You can find us on Twitter or Instagram @Unsung__History, or on Facebook @UnsungHistoryPodcast. To contact us with questions, corrections, praise, or episode suggestions, please email Kelly@UnsungHistoryPodcast.com. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate, review, and tell everyone you know. Bye!

Transcribed by https://otter.ai

Ashley Rose Young

I’m a cultural and social historian of the United States and my research explores the intersection of race, ethnicity, and gender in American food culture and economy. My first book, Nourishing Networks: The Public Culture of Food in New Orleans, (Oxford University Press, Fall 2025), examines how daily practices of food production and distribution shaped the development of New Orleans’ public culture and reveal how power operated in unexpected ways along the networks that fed New Orleans.

I earned a Ph.D. in History from Duke University, an M.A. in History from Duke University, a B.A. in History from Yale College, and was a visiting scholar at Oxford University.

In my current role as Curator of American History in the Rare Book & Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress, I have the extraordinary opportunity to steward and interpret one of the world’s most significant collections of rare books and manuscripts related to American life. My role involves curating exhibitions, acquiring rare materials, conducting original research, and expanding public and scholarly engagement with the collections.

I collaborate with colleagues across the institution to develop interpretive projects that illuminate the historical and cultural richness of the Library’s holdings—from early American print culture to political and food history. I also support teaching and outreach initiatives, respond to research inquiries, and contribute to the long-term preservation of rare materials that document the many voices and experiences that have shaped the U… Read More